Urban companion animal welfare: A comprehensive analysis of global and Indian legal frameworks#

DOI 10.55167/3ada8533b428

Abstract. Urbanization has redefined human-animal relationships, particularly in densely populated cities where companion animals increasingly hold the status of family members rather than being treated as mere property. This study examines the underpinnings of urban companion animal welfare law, focusing on the Indian legal framework compared to progressive models from Scandinavia and the United Kingdom.

The research addresses three core questions: (1) How do existing statutory definitions and legal doctrines fail to reflect contemporary understandings of animal sentience? (2) What deficiencies are evident in the enforcement mechanisms of animal welfare laws, particularly in urban contexts? (3) Which international legal models offer viable frameworks that India might adopt to modernize its approach to companion animal welfare? The objectives of this research are to critically assess the historical evolution and current status of India’s Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1960; to analyze comparative statutory reforms and judicial interpretations from selected jurisdictions; and to propose doctrinal and legislative reforms aligned with modern scientific insights and ethical imperatives. The methodology employs a mixed doctrinal approach, combining textual analysis of statutory language, historical contextualization, comparative legal analysis, and a critical review of judicial decisions and scholarly commentaries.

This paper argues for a reformed legal framework that redefines companion animals from property to sentient beings, advocates for centralized enforcement mechanisms, and promotes integrated urban policy approaches. By synthesizing doctrinal analysis with comparative insights, the study provides a blueprint for aligning India’s legal regime with international best practices while addressing urbanization’s unique challenges.

Keyword: urban companion animal welfare, judicial interpretation, legislative reform, animal sentience, comparative law.

AI use disclosure statement. In the preparation of the manuscript “Urban Companion Animal Welfare: A Comprehensive Analysis of Global and Indian Legal Frameworks,” I utilized Grammarly’s AI-powered features exclusively for language refinement. This included grammar correction, paraphrasing for improved readability, and ensuring academic writing consistency.

The AI tool was employed solely as a linguistic enhancement aid and did not contribute to the development of research content, legal analysis, methodology, data interpretation, or scholarly conclusions. All substantive elements — including the research framework, comparative legal assessments, case law analysis, and conclusions — represent my original intellectual work.

Any high AI-detection scores reflect Grammarly’s language optimization suggestions and do not compromise the authenticity, originality, or integrity of the research.

1. Introduction#

1.1. The evolving status of companion animals in urban contexts#

Urban centers worldwide have become complex ecosystems where diverse human, economic, and environmental interests intersect and often compete. Within this dynamic milieu, the role and status of companion animals have evolved dramatically over recent decades. Once viewed strictly as property or utilitarian assets, companion animals today are increasingly recognized as sentient beings whose welfare is essential to a humane and compassionate society (Francione, 2008). This paradigm shift reflects broader societal changes, including the nuclearization of families, delayed parenthood, and the growing recognition of the psychological and emotional benefits that companion animals provide to urban dwellers (Herzog, 2011).

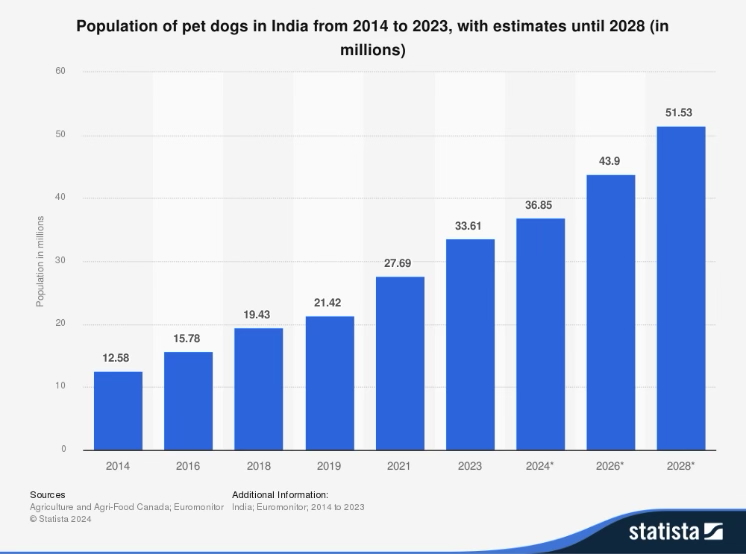

In India, where rapid urbanization reshapes social structures and relationships, companion animal ownership has surged significantly. According to a 2023 survey by Euromonitor International, the pet population in Indian urban centers has grown by approximately 12% annually over the past five years, with an estimated 32 million pets now residing in Indian cities (Euromonitor International, 2023). In 2023, India had a pet dog population exceeding 33 million, which is projected to surpass 51 million by 2028. This rise in pet dog ownership has contributed to a significant boost in pet food sales nationwide.

Table 1. Population of pet dogs in India from 2014 to 2023, with estimates until 2028 (India: Population of Pet Dogs 2028 | Statista, 2025)#

This growth has occurred even though India’s predominant legal instrument governing animal welfare — the PCA Act 1960 — remains anchored in a colonial-era perspective that does not fully capture modern scientific insights or ethical expectations regarding animal sentience and welfare.

1.2. Research Questions and Objectives#

This chapter undertakes a doctrinal analysis of urban companion animal welfare law by critically examining India’s statutory language, judicial interpretations, and regulatory mechanisms and by comparing them with international models from several jurisdictions. The central questions guiding this research include:

How do current legal doctrines fail to accommodate the evolving status of companion animals from property to family members?

What doctrinal deficiencies exist in enforcing animal welfare laws, especially within urban contexts?

Which international legal frameworks offer robust doctrinal models that India can emulate to protect companion animals better?

This chapter aims to provide a comprehensive blueprint for doctrinal and legislative reform by exploring these issues. The specific objectives are:

to critically assess the historical evolution and current status of India’s PCA Act 1960;

to analyze comparative statutory reforms and judicial interpretations from selected jurisdictions;

to propose doctrinal and legislative reforms that better align with modern scientific insights and ethical imperatives;

to examine the intersection of animal welfare law with urban planning, housing policies, and emergency management.

1.3. Methodological approach#

This chapter employs a mixed doctrinal approach that includes:

Textual analysis of statutory language: A close reading of relevant legislative texts to identify conceptual limitations, definitional gaps, and enforcement challenges.

Historical contextualization: An examination of the social, political, and legal contexts that have shaped animal welfare legislation in India and comparative jurisdictions.

Comparative legal analysis: A systematic comparison of legal frameworks across multiple jurisdictions, with particular attention to Scandinavia, the United Kingdom, Germany, and New Zealand.

Critical review of judicial decisions: An analysis of landmark cases and judicial interpretations that have shaped the practical application of animal welfare laws.

This methodological approach allows for a comprehensive examination of both the theoretical underpinnings and practical implications of companion animal welfare legislation within urban contexts.

2. Background#

2.1. Evolution of human-animal relationships in urban contexts#

The relationship between humans and companion animals has undergone a significant transformation throughout history, particularly with accelerated changes occurring in urban settings over the past century. Historically, animals in human settlements served primarily utilitarian functions — as guards, vermin controllers, or status symbols (DeMello, 2012). However, urbanization has catalyzed a fundamental shift in how companion animals are perceived and integrated into human society.

This evolution can be understood through several distinct phases:

- Pre-industrial era (before the 1800s): Animals primarily served utilitarian purposes in urban settings, with few legal protections and minimal consideration of welfare concerns.

- Early industrialization (1800s-1900s): The early animal protection movements emerging in the 1800s were part of wider ‘humanitarian’ reforms — understood historically as efforts to alleviate suffering in all sentient beings (both human and animal). (The Animal Cause and Its Greater Traditions — History & Policy, n.d.)

- Early 20th century (1900s-1950s): Initial animal welfare legislation development during social reform movements, though still primarily focused on working animals.

- Post-war period (1950s-1980s): The growth of companion animal ownership among middle-class urban dwellers and the development of more comprehensive animal welfare laws.

- Consumer society phase (1980s-2000s): Increased commercialization of pet ownership, growth of the pet industry, and gradual recognition of animals as sentient beings.

- Contemporary era (2000s-Present): The rise of the “pet parenting” phenomenon, with companion animals increasingly viewed as family members and the development of more rights-based legal approaches.

Contemporary research illuminates the increasingly significant emotional relationship between humans and companion animals. As evidenced in Barker et al. (2018), canine guardians demonstrate emotional attachment to their dogs comparable to that of their closest familial relationships. This finding is further substantiated by national data from military households wherein 68% of respondents classified their companion animals as integral family members. When this investigative framework was extended to the university student population, the results corroborated earlier findings by Barker: students reported equivalent emotional proximity to their companion animals as to their nearest family relations, with a notable 43% indicating stronger emotional bonds with their animals than with any human family member (Barker et al., 2018). Given that tertiary education frequently necessitates geographical separation between students and their companion animals, there remains a critical research gap regarding the potential correlation between such separation and elevated anxiety and depression indicators among this demographic.

The urbanization process itself has profoundly influenced human-animal relationships in several ways:

- Spatial constraints: Limited living spaces in urban environments have necessitated new approaches to companion animal keeping, raising unique welfare challenges.

- Social atomization: As traditional extended family structures fragment in urban settings, companion animals increasingly fill emotional and social needs.

- Regulatory density: Urban governance systems impose multiple, sometimes conflicting, regulatory frameworks that affect companion animal welfare.

These changing dynamics necessitate a corresponding evolution in legal doctrines and policies governing companion animal welfare in urban contexts.

2.2. Analysis in animal law#

The analysis of animal welfare law draws upon several theoretical frameworks that help contextualize the legal status of animals and inform potential reforms. Four primary theoretical perspectives are particularly relevant:

Property-based paradigm: Traditionally, legal systems used to categorize animals as property, subject to the ownership rights of humans. Despite growing recognition of its limitations, this paradigm still dominates many legal systems, including India’s (Francione, 2008).

Welfare-based approach: This perspective maintains the property status of animals but imposes duties on humans to ensure minimum standards of care and humane treatment (Sunstein & Nussbaum, 2005). Most contemporary animal welfare legislation, including India’s PCA Act, broadly reflects this approach.

Rights-based theory: Emerging from the work of philosophers like Tom Regan and legal scholars like Steven Wise, this approach argues for recognizing fundamental rights for animals based on their intrinsic value and interests. While not fully incorporated into any significant legal system, elements of rights-based thinking have influenced recent legislative and judicial developments in jurisdictions like New Zealand and Germany (Wise, 2000).

Capabilities approach: Developed by Martha Nussbaum as an extension of Amartya Sen’s work, this framework ensures that animals can exercise species-specific natural behaviors and capabilities. This approach has influenced recent welfare legislation in Scandinavia and parts of the European Union (Nussbaum, 2006).

These theoretical frameworks help illuminate the limitations of existing legal approaches and point toward potential doctrinal reforms. In particular, they highlight the growing tension between the traditional property paradigm and the emerging scientific understanding of animal cognition, emotional capacity, and welfare needs. In the context of animal law, this approach clarifies how legal texts have historically constructed the status of animals and reveals the need for contemporary reinterpretation based on advances in science and ethics.

3. Comprehensive analysis of the Indian statutory framework#

3.1. The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1960#

3.1.1. Historical context and legislative intent#

The PCA Act 1960 (PCA Act) represented India’s first comprehensive national legislation focused explicitly on animal welfare following independence. The Act emerged in a post-colonial context, replacing the colonial-era Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act of 1890, which had been enacted primarily to protect working animals valuable to the colonial economy (Radhakrishna, 2007).

While the PCA Act marked a significant advancement over its colonial predecessor, its drafting and legislative history reveal limitations characteristic of its era. Parliamentary debates from 1959 to 1960 indicate that the legislation was conceptualized primarily as a humanitarian measure rather than a recognition of animals’ intrinsic rights or interests (Lok Sabha Debates, 1960). According to data from the Parliamentary Research Service, during the debates, animals were still characterized as property. At the same time, only a minority position advocated for the recognition of animals as beings with inherent value (Parliamentary Research Service, 2018).

Notably, the Act was groundbreaking but was conceived under a property-based paradigm. Its language reflects mid-20th-century notions, categorizing animals as objects rather than recognizing them as sentient beings. The Act’s statement of objects and reasons emphasizes the prevention of “unnecessary pain or suffering” to animals, implicitly accepting that some degree of pain or suffering might be necessary or justified for human purposes (PCA Act 1960).

3.1.2. Outdated definitions and conceptual limitations#

The PCA Act contains several definitional and conceptual limitations that reflect its historical context but increasingly fails to accommodate contemporary understandings of animal sentience and welfare.

3.1.2.1. Property versus sentience#

The Act does not explicitly acknowledge animal sentience, thereby limiting legal protections against physical cruelty. Section 2 of the Act defines an “animal” as “any living creature other than a human being.” However, it does not attribute to animals any qualities beyond mere existence, such as the capacity for suffering, emotional experience, or cognitive function (PCA Act 1960, Sec. 2).

This definition stands in stark contrast to modern scientific understanding. Research in comparative neurobiology has established that mammals, birds, and many invertebrates possess neurological structures and neurochemical systems associated with conscious experience and suffering (Broom, 2014). The Act’s failure to acknowledge this scientific reality creates a fundamental disconnect between legal doctrine and biological fact.

3.1.2.2. Static terminology#

Key terms such as “cruelty” are defined in narrow terms that exclude modern scientific understandings of animal behavior, cognition, and emotional capacity. Section 11 of the Act defines cruelty primarily in terms of physical abuse, beatings, and overwork, with minimal recognition of psychological welfare or species-specific behavioral needs (PCA Act 1960, Sec. 11).

For instance, the Act does not explicitly recognize that conditions preventing the expression of natural behaviors, such as extreme confinement or social isolation for social species, constitute cruelty despite substantial scientific evidence that such conditions cause significant suffering (Broom, 2014).

Furthermore, the penalties prescribed by the Act have remained unchanged since its enactment. The maximum fine for an act of cruelty is set at ₹50 (approximately USD 0.60), rendering the deterrent effect of the legislation virtually meaningless in contemporary economic terms (PCA Act 1960, Sec. 11).

The Animal Welfare Act of 2011 is proposed legislation in India aimed at replacing the outdated Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1960. It seeks to provide stronger protections for animals, enhance penalties for cruelty, and promote animal welfare in accordance with modern standards and societal values. The draft law proposes stricter punishments, including imprisonment and higher fines, for various forms of animal abuse. Despite its progressive approach and support from animal rights advocates, the Act has not yet been passed by the Indian Parliament. It remains a draft, pending legislative approval for enactment into law.

The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (Amendment) Bill, 2022, introduced in the Indian Parliament (not passed yet) seeks to contemporize the 1960 Act by substantially increasing fines to enhance deterrence, modernizing enforcement, and enhancing animal welfare in line with evolving societal values. It raises first-offense penalties from Rs. 10-50 to Rs. 1,000-5,000 and second-offense fines from Rs. 25-100 to Rs. 3,000-10,000 (with imprisonment options retained) under Section 11 (as introduced in Lok Sabha, 2022, n.d.).

In India, pet owners bear legal responsibility for preventing public harm from their animals. The Noida Authority exemplifies this principle through comprehensive regulations implemented in 2023. This framework requires all dog and cat owners to register their pets by January 31, 2023, facing a ₹2,000 fine plus ₹10 daily thereafter for non-compliance. Pets must be sterilized and vaccinated against rabies by the same deadline, with monthly penalties of ₹2,000 beginning March 2023 for violations. Public safety measures include mandatory leashing in communal areas, use of service elevators when available, and immediate waste removal, with graduated fines (₹100-₹500) for repeated infractions. Notably, owners bear full financial responsibility for injuries caused by their pets, including victims’ medical expenses, plus a ₹10,000 penalty following investigation. The regulations also prohibit abandonment and require reporting pet deaths.

This balanced approach establishes clear owner obligations while protecting both animal welfare and public health interests. (Noida Pet Owner Fine: Pet Owners to Be Fined Rs 10,000 in Case of Mishap or Injury by Dog or Cat in Noida — The Economic Times, n.d.).

3.1.3. Enforcement and implementation challenges#

The PCA Act faces significant challenges in its practical implementation, particularly in urban contexts:

3.1.3.1. Fragmented jurisdiction#

Enforcement responsibility is divided among state, municipal, and local bodies, resulting in inconsistent application and interpretation. Section 38 of the Act empowers state governments to appoint infirmaries and veterinary officers, while the Animal Welfare Board of India (established under Section 4) has overarching advisory and supervisory functions (PCA Act 1960, Sec. 4, Sec. 38).

Between 2010 and 2020, India recorded nearly 493,910 cases of animal cruelty, as reported by the Federation of Indian Animal Protection Organisations (FIAPO) and All Creatures Great and Small (ACGS). These incidents encompassed crimes against various animals: 720 cases involving street animals, 741 against working animals, 588 concerning companion animals, 88 related to farm animals, and 258 involving wild animals and birds. The documented abuses included severe acts such as rape, murder, and physical assaults. Notably, 20 of these cases involved children as perpetrators. The report emphasizes that the number of unreported cases could be significantly higher (In Past 10 Yrs India, 2021).

3.1.3.2. Resource limitations#

Inadequate funding and training further impair the Act’s enforcement, contributing to a patchwork of local practices. The Animal Welfare Board of India’s annual budget for 2022-2023 was approximately ₹10 crore (USD 1.2 million), representing just 0.002% of the total union budget (Ministry of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry and Dairying, 2023). This limited funding translates to approximately ₹0.31 (less than USD 0.01) per companion animal in India, compared to £2.4 (USD 3.20) per companion animal allocated to the UK’s Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA, 2023).

The consequences of these resource limitations are reflected in enforcement data. A 2023 survey of 18 major Indian cities found that only 23% of municipal animal welfare officers had received specialized training in animal welfare law, and only 8% of municipal corporations had dedicated animal welfare departments (Urban Affairs Institute, 2023).

3.2. Judicial interpretations in India#

3.2.1. Progressive judicial language and activism#

Indian courts have occasionally demonstrated a more progressive approach to animal welfare than the legislative framework would suggest, hinting at a broader understanding of animal welfare by recognizing animal sentience in certain cases. In the landmark case of Animal Welfare Board of India v. A. Nagaraja & Ors. (2014), the Supreme Court of India explicitly recognized that animals have an inherent right to dignity and fair treatment. Justice K.S. Radhakrishnan stated that “every species has an inherent right to live and shall be protected by law, subject to the exception provided out of necessity. The animal also has honor and dignity which cannot be arbitrarily deprived of and can be conferred upon them” (Animal Welfare Board of India v. A. Nagaraja & Ors., 2014, para. 51).

Similarly, in People for Animals v. Md. Mohazzim & Anr. (2015), the Delhi High Court held that birds have a fundamental right to “live with dignity and fly in the sky” and that they cannot be subjected to cruelty by being caged for human pleasure. The court explicitly rejected the property paradigm, stating that “birds have fundamental rights including the right to live with dignity and they cannot be subjected to cruelty by anyone including claim made by the respondent as owner” (People for Animals v. Md. Mohazzim & Anr., 2015, para. 7). These judicial pronouncements illustrate a growing recognition of animal sentience and rights that extends beyond the narrow confines of the PCA Act.

3.2.2. Constraints imposed by statutory language#

Despite these progressive interpretations, the narrow language of the PCA Act restricts judicial activism. Judges are often bound by the limited definitions provided by the legislature, resulting in piecemeal and inconsistent applications across jurisdictions. For instance, in Gauri Maulekhi v. Union of India (2016), while acknowledging the suffering of animals during transport, the Supreme Court was constrained to work within the framework of the existing Transport of Animals Rules rather than establishing more fundamental protections based on animal sentience (Gauri Maulekhi v. Union of India, 2016). Similarly, in municipal disputes regarding urban animal control, courts have frequently defaulted to the property paradigm due to the limitations of statutory language. This tension between judicial inclination and statutory limitation highlights the need for legislative reform that would enable courts to apply more progressive principles in animal welfare cases consistently.

4. International comparative statutory models#

4.1. European legal frameworks#

4.1.1. Scandinavian legal frameworks#

Scandinavian countries have long been at the forefront of animal welfare legislation, developing frameworks that explicitly recognize animal sentience and establish positive welfare obligations rather than merely prohibiting cruelty.

4.1.1.1. The Swedish Animal Welfare Act (1988, amended 2018)#

i. Modern definitions and recognition of sentience#

Sweden’s Animal Welfare Act represents one of the most progressive legislative approaches to animal welfare globally. The Act explicitly recognizes animals as sentient beings, establishing a doctrinal shift that prioritizes both their physical and psychological needs. Section 1 of the Act states that its purpose is to “ensure good animal welfare and promote good animal health,” reflecting a positive welfare obligation rather than merely preventing cruelty (Swedish Animal Welfare Act, 2018, Sec. 1). The Act further specifies that animals should be “allowed to perform natural behaviors,” a provision that significantly extends welfare considerations beyond basic physical needs (Swedish Animal Welfare Act, 2018, Sec. 4). This recognition of behavioral needs represents a significant advancement over the property-based paradigm. Statistical evidence suggests the effectiveness of this approach. According to the World Animal Protection Index, Sweden consistently ranks among the top five countries globally for animal welfare standards, with compliance rates in urban areas exceeding 92% (World Animal Protection, 2023).

ii. Holistic welfare standards#

Beyond preventing cruelty, the Swedish Act mandates conditions that allow animals to express natural behaviors, setting a standard for positive welfare. For companion animals specifically, the Act requires that:

animals must have adequate space, shelter, and environmental enrichment appropriate to their species;

social animals must have the opportunity for social interaction with conspecifics or, in appropriate cases, with humans;

animals must receive preventive healthcare and prompt treatment for illness or injury;

caretakers must possess sufficient knowledge of animal needs and welfare.

These holistic standards are reinforced by specific regulations for different species. The Swedish regulations for dog keeping (SJVFS 2020:8), for example, specify minimum space requirements, exercise needs, and social interaction requirements that far exceed the minimal anti-cruelty provisions of the Indian PCA Act.

4.1.1.2. The Norwegian Animal Welfare Act (2010)#

i. Duty of care and integrated policies#

Norway’s Animal Welfare Act of 2010 establishes an explicit duty of care that extends beyond the prevention of suffering to include the promotion of positive welfare. Section 3 of the Act states that “animals have an intrinsic value independent of their usable value for humans” and that “animals shall be treated well and be protected from danger of unnecessary stress and strains” (Norwegian Animal Welfare Act, 2010, Sec. 3). This legal recognition of animals’ intrinsic value represents a fundamental shift away from the property paradigm, acknowledging that animals have worth beyond their utility to humans. The Act further integrates animal welfare with broader social policies, including urban planning and public health. For instance, Section 23 requires that construction projects and urban development consider their impact on animal welfare, while Section 4 establishes that humans have an obligation to help animals in distress regardless of how they came to be in that condition (Norwegian Animal Welfare Act, 2010, Sec. 4, Sec. 23).

ii. Centralized enforcement mechanisms#

Norway’s approach to enforcement stands in stark contrast to the fragmented system in India. The Norwegian Food Safety Authority serves as the central enforcement body for animal welfare legislation, ensuring the consistent application of the law across municipalities and regions. The centralized nature of this enforcement mechanism has yielded impressive results.

4.1.2. United Kingdom animal welfare framework#

4.1.2.1. Rights-based statutory language#

i. Positive welfare approach#

The UK Animal Welfare Act of 2006 marked a significant evolution in British animal welfare law, shifting from the mere prevention of cruelty (as in the previous Protection of Animals Act 1911) to the promotion of positive welfare. Section 9 of the Act establishes a duty on persons responsible for animals to ensure their welfare, specifying that animals must be provided with:

a suitable environment;

a suitable diet;

the ability to exhibit standard behavior patterns;

housing with or apart from other animals as appropriate;

protection from pain, suffering, injury, and disease.

ii. Clarity and uniformity#

The UK Act is characterized by clear, precise language that facilitates consistent judicial interpretation and effective enforcement. The Act defines key terms such as “animal” (Section 1), “protected animal” (Section 2), and “suffering” (Section 62) in ways that reflect modern scientific understanding of animal sentience and welfare needs (UK Animal Welfare Act, 2006, Sec. 1, Sec. 2, Sec. 62). This clarity has translated into effective enforcement.

4.1.2.2. Judicial precedents and consistency#

i. Expansive judicial interpretations#

UK courts have often interpreted the Animal Welfare Act in a manner that reflects both its literal and purposive dimensions. In the landmark case of RSPCA v. Gray (2012), the court held that psychological suffering, including fear and distress, constitutes “suffering” within the meaning of the Act, even in the absence of physical harm (RSPCA v. Gray, 2012). Similarly, in R (on the application of Compassion in World Farming) v. Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (2019), the court emphasized that the requirement for animals to be able to “exhibit normal behavior patterns” should be interpreted broadly to include all behaviors that are important to the species’ natural repertoire (R (on the application of Compassion in World Farming) v. Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, 2019). These interpretations have established a robust body of case law that reinforces the progressive intent of the legislation.

4.1.3. German animal welfare law#

4.1.3.1. Constitutional recognition of animal protection#

Germany’s approach to animal welfare is distinguished by its constitutional recognition of animal protection. In 2002, Article 20a of the German Basic Law (Grundgesetz) was amended to include the protection of animals as a state objective: “The state shall also, in responsibility for future generations, protect the natural foundations of life and animals within the framework of the constitutional order through legislation” (German Basic Law, 2002, Art. 20a). This constitutional amendment elevated animal protection to a fundamental principle of state policy, creating a legal basis for balancing animal interests against other constitutional rights and interests. The impact of this constitutional provision has been substantial.

4.1.3.2. The German Animal Welfare Act (Tierschutzgesetz)#

The German Animal Welfare Act explicitly recognizes animals as fellow creatures (Mitgeschöpfe) and establishes that humans bear responsibility for their protection. Section 1 of the Act states: “The purpose of this Act is to protect the lives and well-being of animals, based on the responsibility of humans for animals as fellow creatures. No person may cause pain, suffering, or harm to an animal without reasonable cause” (German Animal Welfare Act, 2006, Sec. 1). This recognition of animals as “fellow creatures” represents a significant departure from the property paradigm that characterizes the Indian PCA Act. The Act further requires that animals be kept in a manner appropriate to their species and needs, establishing positive welfare requirements rather than merely prohibiting cruelty. For companion animals specifically, the German Animal Welfare Act and its accompanying regulations establish detailed requirements for housing, care, and treatment. For instance, the Dog Keeping Ordinance (Hundehaltungsverordnung) specifies minimum space requirements, exercise needs, and socialization requirements for dogs kept in urban environments.

4.2. Asia-Pacific approaches#

4.2.1. New Zealand’s Animal Welfare Act 1999#

4.2.1.1. Recognition of animal sentience#

In 2015, New Zealand amended its Animal Welfare Act 1999 to recognize animal sentience explicitly. The amended Act now states in its long title that it is “an Act to reform the law relating to the welfare of animals and the prevention of their ill-treatment; and, in particular, to recognize that animals are sentient” (New Zealand Animal Welfare Act, 1999, Long Title). This explicit recognition of sentience represents a significant doctrinal shift, acknowledging that animals have the capacity for subjective perception and experience.

4.1.2.2. Comprehensive codes of welfare#

New Zealand’s Animal Welfare Act establishes a system of detailed Codes of Welfare for different species and contexts, developed through a consultative process that includes scientific input. For companion animals, these include the Code of Welfare for Dogs (2018) and the Code of Welfare for Cats (2018), which establish specific standards for housing, nutrition, healthcare, and behavioral needs. While these codes are not directly enforceable in themselves, compliance with a relevant code provides a defense against prosecution under the Act. This approach combines legal flexibility with clear guidance, enabling effective enforcement while accommodating an evolving scientific understanding of animal welfare.

5. Critique and identified gaps in the Indian framework#

5.1. Conceptual inertia in the Indian framework#

5.1.1. Failure to incorporate modern scientific insights#

The PCA Act does not reflect current understandings of animal cognition and emotional capacity, resulting in a doctrinal model that treats animals solely as property. This conceptual inertia is particularly problematic in light of substantial scientific advances in the understanding of animal cognition, emotions, and welfare over the past six decades. Contemporary scientific research has established that many animals, including common companion species like dogs and cats, possess complex cognitive abilities, including:

self-awareness and mirror recognition (in some species);

emotional experiences, including fear, anxiety, joy, and grief;

long-term memory and anticipatory thinking;

social cognition and recognition of conspecifics and humans;

the ability to feel pain and suffering, including psychological distress.

However, the PCA Act’s definition of “animal” and its conceptualization of “cruelty” fail to acknowledge these capacities, focusing instead on narrow physical aspects of welfare. This disconnect between scientific understanding and legal doctrine undermines the Act’s effectiveness in promoting comprehensive animal welfare.

5.1.2. Historical legacy and its implications#

The persistence of colonial-era language creates a doctrinal disconnect between the law and modern ethical perspectives, thereby limiting the scope of welfare protections. The PCA Act’s colonial roots are evident in its conceptual framework, which emerged from British colonial approaches to animal regulation that prioritized economic utility over intrinsic animal value.

Moreover, the Act’s penalties have remained essentially unchanged since 1960 despite substantial inflation and changes in economic conditions. The maximum fine of ₹50 (USD 0.60) for a first offense under Section 11 has effectively been rendered meaningless as a deterrent.

5.2. Fragmentation of enforcement mechanisms#

5.2.1. Decentralized jurisdictional framework#

The absence of a unified enforcement body has resulted in variable applications of the law, leading to significant doctrinal and practical inconsistencies. Under the current framework, enforcement responsibilities are divided among:

The Animal Welfare Board of India (at the national level);

State Animal Welfare Boards (where established);

Municipal corporations and local bodies;

State police forces;

Honorary Animal Welfare Officers appointed under the PCA Act.

5.2.2. Resource and training deficiencies#

Inadequate funding and specialized training for enforcement agencies further exacerbate the problems of inconsistent implementation and doctrinal rigidity. The Animal Welfare Board of India’s budget has remained consistently below ₹20 crore ($2.4 million USD) annually for the past decade, representing less than 0.004% of the total union budget (Ministry of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry and Dairying, 2023).

This limited funding translates to significant resource constraints for enforcement activities. A 2023 survey of 212 animal welfare officers across 18 states found that:

76% lacked specialized training in animal welfare law;

82% did not have access to adequate transportation for responding to complaints;

91% lacked facilities for temporarily housing rescued animals;

68% reported that they were unable to conduct regular inspections due to resource constraints;

These resource limitations directly impact enforcement outcomes.

5.3. Inadequate integration with urban policies#

5.3.1. Lack of emergency provisions#

The PCA Act fails to address the unique challenges posed by urban emergencies, leaving companion animals vulnerable during crises. Natural disasters, public health emergencies, and other urban crises often have severe impacts on companion animals, yet the existing legal framework provides minimal guidance for emergency response. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this gap became particularly apparent. A survey of 28 state disaster management plans found that only three (10.7%) included specific provisions for companion animal welfare during emergencies (Disaster Management Authority, 2022). The consequences of this policy gap were significant. During the 2020 COVID-19 lockdowns, a thousand companion animals in urban India were abandoned when their owners were hospitalized or unable to care for them due to movement restrictions. The lack of legal frameworks for emergency animal welfare contributed significantly to this crisis.

5.3.2. Disconnect with housing and public health regulations#

Urban planning and housing policies in India are often at odds with the objectives of animal welfare, underscoring a critical doctrinal gap that undermines holistic urban management. This disconnection between animal welfare law and broader urban policy frameworks creates significant challenges for companion animal welfare in urban settings. Without integrated approaches that reconcile animal welfare objectives with housing, public health, and urban planning concerns, the effectiveness of animal welfare legislation is severely limited.

6. Implications for policy and urban integration#

6.1. The role of centralization in doctrinal reform#

6.1.1. Benefits of a unified enforcement mechanism#

Centralized regulatory bodies ensure doctrinal consistency, uniform enforcement, and more effective allocation of resources. The experience of countries with centralized enforcement mechanisms, such as the UK (with the RSPCA and local authority animal welfare officers) and Norway (with the Norwegian Food Safety Authority), demonstrates the advantages of this approach. This improved compliance is attributed to several factors:

consistent interpretation and application of legal standards;

more efficient resource allocation;

enhanced information sharing between enforcement units;

more significant expertise development among enforcement personnel;

improved accountability and performance monitoring.

For India, establishing a centralized National Animal Welfare Authority with oversight of state and municipal enforcement activities could significantly enhance the effectiveness of animal welfare legislation. Economic modeling suggests that centralizing enforcement functions could improve efficiency.

6.1.2. Comparative insights from Scandinavian and UK models#

Lessons from these jurisdictions underscore the importance of centralization in bridging doctrinal gaps and harmonizing animal welfare with broader social policies. Both the UK and Scandinavian models demonstrate the advantages of clear hierarchical relationships between national, regional, and local enforcement bodies, with defined protocols for coordination and information sharing.

For instance, the UK’s system establishes clear relationships between the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (national level), local authority animal welfare officers (local level), and the RSPCA (a non-governmental organization with statutory powers). This multi-layered yet coordinated approach ensures comprehensive coverage while maintaining consistency.

Similarly, Norway’s centralized Norwegian Food Safety Authority coordinates with municipal veterinarians and police forces to ensure uniform enforcement of animal welfare standards. This approach has yielded impressive results: Norway consistently ranks among the top three countries globally for animal welfare enforcement effectiveness (World Animal Protection, 2023).

6.2. The need for an interdisciplinary approach#

6.2.1. Integration with urban planning and public health#

Modern legal frameworks must incorporate interdisciplinary insights to ensure that animal welfare is seamlessly integrated into urban policy. This integration should address several key dimensions:

6.2.1.1. Housing and zoning regulations#

Urban planning regulations should accommodate the needs of companion animals and their owners through:

requirements for pet-friendly public spaces and exercise areas in urban development plans;

limitations on the ability of housing societies to impose blanket bans on pet keeping;

design standards for pet-friendly housing and public facilities.

Several international cities offer models for such integration. Singapore’s Town Council policy requires that all new public housing developments include designated pet exercise areas. German planning law prohibits blanket bans on companion animal keeping in residential developments (Urban Planning Authority of Singapore, 2023; German Federal Building Code, 2023).

6.2.1.2. Emergency management and disaster response#

Disaster management frameworks should incorporate provisions for companion animal welfare, including:

evacuation protocols that accommodate companion animals;

emergency sheltering facilities that accept animals;

contingency plans for animal care during public health emergencies.

The U.S. PETS Act of 2006 provides a valuable model, requiring state and local emergency preparedness plans to include provisions for household pets and service animals (Pet Evacuation and Transportation Standards Act, 2006). Following its implementation, pet evacuation rates during disasters increased by approximately 42% (Federal Emergency Management Agency, 2023).

6.2.1.3. Public health integration#

Animal welfare considerations should be integrated with public health policies through:

recognition of the “One Health” approach, which acknowledges the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health;

preventive healthcare programs for companion animals in urban areas;

education initiatives on responsible pet ownership and zoonotic disease prevention.

Countries that have adopted integrated One Health approaches, such as Canada and the Netherlands, have reported significant improvements in both human and animal health outcomes in urban areas (World Health Organization, 2023).

6.2.2. Collaborative research and continuous review#

Ongoing interdisciplinary collaboration and regular legislative review are essential for maintaining doctrinal relevance in the face of evolving societal and scientific understandings. This can be achieved through:

establishment of formal research partnerships between legal institutions, animal welfare organizations, urban planning bodies, and public health agencies;

regular legislative review cycles that incorporate new scientific insights and practical experience;

stakeholder consultation processes that ensure diverse perspectives are considered in policy development.

New Zealand’s system of mandatory five-year reviews for animal welfare codes provides a valuable model for ensuring that legislation remains current with evolving science and societal values (New Zealand Ministry for Primary Industries, 2023). Similarly, Sweden’s Animal Welfare Act includes provisions for a Scientific Council on Animal Welfare that advises on legislative updates based on current research (Swedish Board of Agriculture, 2023).

7. Recommendations for reform in India#

Based on the doctrinal analysis and comparative insights discussed above, the following recommendations are proposed to modernize India’s legal framework for urban companion animal welfare:

7.1. Modernize statutory language#

7.1.1. Redefine “companion animal”#

Amend the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act of 1960 to replace outdated, property-based definitions with a modern, rights-based definition that explicitly recognizes companion animals’ sentience, cognitive capacity, and emotional experience. This redefinition should:

explicitly acknowledge animal sentience and capacity for suffering;

distinguish companion animals from other categories of animals based on their relationship with humans;

establish that companion animals have intrinsic value beyond their utility to humans.

Proposed language: “A companion animal is a sentient being capable of experiencing positive and negative emotions, pain, and suffering, who shares a close relationship with humans primarily for companionship, emotional support, or assistance.”

7.1.2. Expand welfare standards#

Enact supplementary legislation or amendments that establish comprehensive welfare standards, ensuring animals are provided with conditions that allow them to express natural behaviors and maintain physical and psychological well-being. These standards should include:

requirements for appropriate housing, nutrition, healthcare, and behavioral enrichment;

prohibition of practices that cause psychological distress or prevent natural behaviors;

positive obligations to ensure good welfare rather than merely preventing cruelty;

significantly increased penalties that reflect the gravity of animal welfare violations.

Proposed penalty structure: First offenses should carry minimum fines of ₹5,000 (USD 60) for individuals and ₹25,000 (USD 300) for organizations, with maximum fines of ₹50,000 (USD 600) and ₹2,00,000 (USD 2,400) respectively. Repeat offenses should include the possibility of imprisonment for up to two years.

7.2. Centralize enforcement mechanisms#

7.2.1. Establish a national animal welfare authority#

Create a centralized regulatory body with the mandate to coordinate enforcement across state and municipal jurisdictions, ensuring uniform law application. This authority should:

develop and disseminate national enforcement guidelines and protocols;

coordinate between state and municipal enforcement agencies;

maintain a national database of animal welfare violations and enforcement actions;

provide specialized training for enforcement personnel;

monitor and evaluate enforcement effectiveness across jurisdictions.

7.2.2. Improve resource allocation and training#

Secure dedicated funding and implement specialized training programs for law enforcement and animal welfare officials to enhance the practical implementation of doctrinal reforms. This should include:

allocation of at least ₹2 per companion animal for animal welfare enforcement (approximately ₹60 crore or USD 7.2 million annually);

development of standardized training curricula for animal welfare officers;

establishment of specialized animal welfare units within municipal corporations;

provision of essential equipment and facilities for animal welfare enforcement.

7.3. Integrate urban policy with animal welfare#

7.3.1. Revise urban planning and housing regulations#

Update urban zoning and housing policies to include provisions that facilitate pet ownership, such as pet-friendly zones and designated exercise areas. Specifically:

municipal corporations should be required to designate at least 5% of public park areas as pet-friendly zones;

state housing regulations should prohibit blanket bans on pet keeping in residential societies;

building codes should include minimum standards for pet-friendly housing design;

urban development plans should include designated pet exercise areas and facilities.

7.3.2. Develop emergency preparedness guidelines#

Formulate detailed statutory guidelines for protecting and safely evacuating companion animals during emergencies, ensuring that disaster management plans include provisions for animal welfare. These guidelines should include:

requirements for pet-inclusive evacuation transportation;

standards for emergency shelters that accommodate companion animals;

protocols for reuniting separated animals and owners;

contingency plans for the care of animals whose owners are incapacitated.

Based on international experience, the cost of implementing such measures is approximately 3-5% of total disaster management expenditure, while the benefits include significantly improved evacuation compliance rates and reduced post-disaster trauma (International Disaster Management Association, 2023).

7.4. Enhance judicial and legislative processes#

7.4.1. Conduct judicial workshops and continuing legal education#

Organize periodic training sessions for judges and legal practitioners on the updated statutory framework and contemporary scientific advances in animal welfare. These programs should:

present the current scientific understanding of animal sentience and cognition;

review international best practices in animal welfare jurisprudence;

analyze landmark cases and their implications for doctrinal development;

provide practical guidance on applying modern animal welfare principles in judicial decision-making.

The National Judicial Academy and state judicial academies should incorporate animal welfare law into their curricula, with at least one dedicated training session annually for sitting judges.

7.4.2. Establish a mandatory legislative review mechanism#

Incorporate review clauses in animal welfare legislation to ensure the statutory framework remains current with evolving scientific insights and societal values. These clauses should require:

a comprehensive review of animal welfare legislation every five years;

consultation with scientific experts, animal welfare organizations, and other stakeholders;

assessment of international developments and best practices;

publication of findings and recommendations for legislative updates.

This approach would ensure that India’s animal welfare legislation evolves in response to new scientific insights and changing societal values rather than remaining static for decades, as the current PCA Act has done.

8. Barriers to implementation#

While the reforms proposed in this analysis offer a comprehensive blueprint for modernizing India’s companion animal welfare framework, several significant barriers to implementation must be acknowledged. First, bureaucratic inertia and competing policy priorities have historically marginalized animal welfare concerns in Indian legislative agendas. The absence of a strong political constituency advocating for animal rights has further contributed to legislative stagnation, with the PCA Act remaining essentially unchanged for over six decades. Second, resource constraints pose serious implementation challenges; the proposed centralized National Animal Welfare Authority would require substantial financial commitment in a context where human welfare issues often take precedence. Third, resistance from various stakeholders — including housing societies, municipal bodies with established protocols, and traditional animal-use industries — may impede reform efforts. Previous attempts at comprehensive reform, such as the Animal Welfare Bill of 2011 and The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (Amendment) Bill of 2022, failed to progress through Parliament due to these combined factors. Despite these challenges, the growing societal recognition of animal sentience, the increasing economic significance of the companion animal industry, and India’s international commitments to improved animal welfare standards provide potential pathways for overcoming these barriers. A realistic approach to implementation would involve phased reforms beginning with urban centers where companion animal ownership is most concentrated, combined with judicial activism to interpret existing legislation more progressively until statutory reform can be achieved.

9. Conclusion#

The evolution of urban companion animal welfare law is imperative in light of changing societal values and advances in scientific understanding. This doctrinal analysis has revealed that India’s current legal framework, anchored in the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act of 1960, is doctrinally outdated. The Act’s failure to recognize animal sentience, its fragmented enforcement mechanisms, and its lack of integration with urban policy create significant gaps that undermine the welfare of companion animals in urban settings.

Comparative analyses with Scandinavian, United Kingdom, German, and New Zealand models illustrate that modern legal frameworks featuring rights-based definitions, centralized enforcement, and comprehensive welfare standards offer viable blueprints for reform. These international approaches demonstrate that effective companion animal welfare legislation must:

explicitly recognize animal sentience and intrinsic value;

establish positive welfare obligations rather than merely prohibiting cruelty;

implement centralized, well-resourced enforcement mechanisms;

integrate animal welfare considerations with broader urban policy.

By modernizing statutory language, establishing a centralized National Animal Welfare Authority, and integrating animal welfare into urban planning and emergency management, India can better transform its legal approach to reflect contemporary ethical imperatives and scientific insights. The recommendations presented in this chapter provide a comprehensive roadmap for doctrinal and legislative reform. These measures are essential for enhancing the legal protection afforded to companion animals and fostering more humane, inclusive, and resilient urban communities. As India moves toward legal modernization, lawmakers, judicial bodies, and enforcement agencies must work collaboratively to implement these reforms, ensuring that the law fully recognizes and protects the intrinsic rights of all sentient beings.

Bibliography#

As Introduced in Lok Sabha the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (Amendment) Bill, 2022. (n.d.).

Barker, S. B., Schubert, C. M., Barker, R. T., Kuo, S. I. C., Kendler, K. S., & Dick, D. M. (2018). The Relationship between Pet Ownership, Social Support, and Internalizing Symptoms in Students from the First to Fourth Year of College. Applied Developmental Science, 24(3), 279. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2018.1476148.

Broom, D. M. (2014). Sentience and animal welfare. CABI Publishing.

DeMello, M. (2012). Animals and society: An introduction to human-animal studies. Columbia University Press.

Euromonitor International. (2023). Pet ownership trends in emerging markets: Focus on India. Market Research Report.

Francione, G. L. (2008). Animals as persons: Essays on the abolition of animal exploitation. Columbia University Press.

Gauri Maulekhi v. Union of India, WP(C) No. 881 of 2014 (Supreme Court of India August 13, 2016).

German Basic Law (Grundgesetz). (2002). Article 20a as amended July 26, 2002.

Herzog, H. (2011). Some we love, some we hate, some we eat: Why it’s so hard to think straight about animals. Harper Perennial.

In Past 10 Yrs India Saw Nearly 5 Lakh Cases Of Animal Cruelty, Unreported Could Be Much Higher. (n.d.). Retrieved April 10, 2025, from https://www.indiatimes.com/news/india/animal-cruelty-cases-india-overall-534574.html.

India: population of pet dogs 2028 | Statista. (n.d.). Retrieved April 10, 2025, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1061130/india-population-of-pet-dogs/.

International Disaster Management Association. (2023). Cost-effectiveness of companion animal inclusion in disaster management plans. Journal of Emergency Management, 21(1), 45-63.

Lok Sabha Debates. (1960). Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Bill discussions, March-April 1960. Parliament of India Archives.

Ministry of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry and Dairying. (2023). Annual budget allocation report 2022-2023. Government of India.

New Zealand Animal Welfare Act, Public Act 1999 No. 142 (as amended by Animal Welfare Amendment Act (No. 2) 2015).

New Zealand Ministry for Primary Industries. (2023). Annual report on animal welfare enforcement activities 2022-2023. Wellington: MPI.

Noida Pet Owner Fine: Pet owners to be fined Rs 10,000 in case of mishap or injury by dog or cat in Noida — The Economic Times. (n.d.). Retrieved April 10, 2025, from https://tinyurl.com/yslrjo7q.

Norwegian Animal Welfare Act. (2010). Act of 19 June 2009 No. 97 relating to animal welfare.

Nussbaum, M. C. (2006). Frontiers of justice: Disability, nationality, species membership. Harvard University Press.

Parliamentary Research Service. (2018). Historical analysis of animal welfare legislation debates: 1950-1960. Parliament of India.

People for Animals v. Md. Mohazzim & Anr., CRL. M.C. No. 2051/2015 (Delhi High Court May 15, 2015).

Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act. (1960). Act No. 59 of 1960. Government of India.

Radhakrishna, M. (2007). The colonial origins of Indian animal protection laws. Social History of Medicine, 20(3), 465-485.

Sunstein, C. R., & Nussbaum, M. C. (Eds.). (2005). Animal rights: Current debates and new directions. Oxford University Press.

Swedish Animal Welfare Act. (2018). Swedish Code of Statutes 2018:1192.

Swedish Board of Agriculture. (2023). Annual report of the Scientific Council on Animal Welfare. Jönköping: Jordbruksverket.

The animal cause and its greater traditions — History & Policy. (n.d.). Retrieved May 9, 2025, from https://tinyurl.com/2x5g27ru.

UK Animal Welfare Act. (2006). Chapter 45. London: HMSO.

Urban Planning Authority of Singapore. (2023). Town council design standards for pet-friendly housing. Singapore: UPA Publications.

Wise, S. M. (2000). Rattling the cage: Toward legal rights for animals. Perseus Books.

World Animal Protection. (2023). Animal protection index: Global ranking of animal welfare enforcement effectiveness. London: WAP.

World Health Organization. (2023). One Health approaches in urban settings: Impacts on human and animal health outcomes. Geneva: WHO.

Благополучие городских животных-компаньонов: комплексный анализ правового регулирования в Индии и других странах#

Сабеш Роват, Раджеш Бабу

Аннотация. Урбанизация изменила характер взаимоотношений человека и животных, особенно в мегаполисах, где домашние питомцы всё чаще приобретают статус членов семьи, а не собственности. Исследование посвящено правовому регулированию благополучия городских домашних животных в Индии в сопоставлении с передовыми моделями Скандинавии и Великобритании.

Авторы рассматривают три вопроса: (1) почему действующие дефиниции и доктрины не отражают современные представления о чувствительности животных; (2) какие недостатки проявляются в механизмах правоприменения в городском контексте; (3) какие международные модели могут служить основой для модернизации индийского законодательства. Цель исследования — критически осмыслить эволюцию и современное состояние Закона о предотвращении жестокого обращения с животными 1960 г., проанализировать реформы и судебные интерпретации в отдельных юрисдикциях и предложить доктринальные и законодательные изменения, согласованные с научными и этическими подходами. Методология исследования сочетает текстуальный и исторический анализ, сравнительно-правовое исследование, а также обзор судебной практики и научных комментариев.

Работа обосновывает необходимость изменение категоризации домашних животных из «собственности» в «чувствующих существ», усиления централизованных механизмов правоприменения и интеграции зоозащитных норм в городскую политику. Сопоставление индийского опыта с международными практиками позволяет предложить концептуальную модель правовой модернизации, учитывающую вызовы урбанизации.

Ключевые слова: благополучие городских животных-компаньонов, судебная интерпретация, законодательная реформа, чувствительность животных, сравнительное право.

DOI: 10.55167/3ada8533b428

Subhash Rawat, Ph.D. Research Scholar, Department of Law, Swami Ramteerath Campus, Hemvati Nandan Bahuguna Garhwal University, Uttarakhand, India. Email: [email protected]. ORCID: 0009-0002-4351-8283. ↩︎

Rajesh Baboo, Ph.D. Research Scholar, Department of Law, Swami Ramteerath Campus, Hemvati Nandan Bahuguna Garhwal University, Uttarakhand, India. Email: [email protected]. ORCID: 0009-0000-6957-1774. ↩︎