Linking policy and practice: exploring professionals’ knowledge, barriers, and experience reporting “The Link” between interpersonal violence and animal abuse#

Aviva Vincent1, Eunice Lee2, Alana Van Gundy3, Lauren Caswell4, Linda Quinn5

DOI 10.55167/31d695a3bd79

Abstract. Objective: “The Link” is a recognized pattern of behavior indicating that pet abuse can signal interpersonal violence, child abuse, or elder abuse. Ohio’s House Bill 33 (HB33) of 2021 aimed to establish mandatory reporting of suspected animal abuse among professionals and serves as a case study for evaluating the effectiveness of such laws. Hypothesis: This exploratory study examines the policy’s intent and potential impact by analyzing demographic variables (age, gender, occupation), awareness of The Link, barriers to reporting, and professional training. Methods: A confidential survey was sent to over 1,500 professionals named as mandatory reporters in HB33, yielding 160 responses. Statistical tests including one-way ANOVA, chi-square, and independent samples t-test examined the associations between demographic variables and key constructs. Following the survey, respondents were also invited to follow-up focus groups (N = 14). Results: The survey respondents were predominantly female (78%) and aged 35 or older. Nearly half worked in human welfare, while 20% were in animal welfare. Awareness of The Link was lower among human welfare workers compared to those in animal-related fields (p < .01). Suspicion of abuse varied by sector, with human welfare workers more likely to suspect abuse based on people’s behavior or appearance, while animal welfare professionals relied on animal behavior and condition (p < .01). Conclusion: Findings highlight the intrinsic connection between human and animal violence, emphasizing the need for a multi-systemic approach. Recommendations include clarifying HB33’s mandatory reporter definition, funding required training, and creating a centralized reporting system. While improvements are needed, HB33 provides a model for replication in other states. Public Significant Statement: This novel study demonstrates the tension between the intention of policy and practice. Though HB33 is a necessary and well-intentioned policy, the professionals who are responsible for reporting suspected animal abuse cannot follow through on mandated reporting if they are unaware and untrained. Policies, such as HB33, will have a greater return on investment if the initial policy includes financial support for its implementation, ongoing training, and data tracking for continuous improvement. Moreover, the lives of humans and animals alike will be saved by community practitioners, as is the intent of the policy.

Keywords: animal law, animal ethics, policy practice, The Link, animal abuse, interpersonal violence, interspecies violence, mandated reporter, multisystemic collaboration, mixed methods.

Statements and Declarations: Competing interests: The authors declare no conflict of interest. There is no funding for this research or publication. Funding: The first author received an internal grant from the university to support this research. Author contributions: Conceptualization, AV; methodology, AV, AvG; formal analysis, AV, EL, AvG; data curation, AV, EL, AvG; writing — original draft preparation, AV, LC, AvG, EL; writing — review and editing, AV, LQ, AvG; project administration, AV. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Institutional Review Board Statement: The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. IRB approval was given by Cleveland State University (IRB-FY2024-249). Human Ethics and Consent to Participate declarations: All participants completed an informed consent prior to survey and/or focus group engagement. Clinical trial number: not applicable. Data Availability Statement: Data are available within the manuscript. Questions and additional information are available on request from the corresponding author. Materials & Correspondence: All communications should be directed to Aviva Vincent, PhD, LSW at [email protected]. Requests for materials, mailing address, and phone number will be addressed via email. Acknowledgments: Gratitude to Cleveland State University for the Faculty Research and Development Program, Vicki Diesner, Esq., for your mentorship, and all community members who gave of their time to support this research and community work.

Introduction#

The Link between interpersonal violence and animal abuse (The Link) constitutes an ongoing public health crisis. “The Link” is also the name of the national organization that seeks to impact and share efforts related to Legislation, Intervention, Networking, and Knowledge (Arkow, 2023). In April of 2021, Ohio HB33, “Establish animal abuse reporting requirements,” was enacted. This novel legislation is the first of its kind to recognize The Link. As with interpersonal violence, animal abuse includes physical, neglect/maltreatment, and sexual abuse. Historically, the first case of child abuse was reported to the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) in 1874, which led to the first child protection agency (ASPCA, 2022). Thus, there has always been a link between animal and child protection services. However, there has yet to be prevention research to understand how interprofessional reporting of interspecies abuse may help save lives.

With pets in more than 70% of U.S. homes, accounting for pets in the lives of people is vital to understanding their needs, decisions, and life choices. Often, people identify their pets as family members, and their choices about family safety involve their pets (Wood et al., 2015). Furthermore, how people choose to allocate financial resources is impacted by pet ownership. The pet economy exceeded $123.6 billion in 2021. The average pet owner budgets and spends roughly $1,500 per year, even in times of financial hardship (American Pet Product Survey, 2022). With this understanding, interprofessional teams are expected to respond to calls and reports of interpersonal and interspecies violence. It is because of this understanding that cross-reporting is identified as the most effective way to address The Link.

Though 95% of reports regarding animals are for neglect (Arkow, 2020), studies are conflicted about an individual’s origin of violence but support The Link as a whole. “…16% of offenders started abusing animals and graduated to violent crimes against humans… [but also] offenders start by hurting other humans and then progress to harming animals” (Robinson & Clausen, 2021). Another challenge is that the understanding of criminal propensity and typology for those who engage in The Link is reliant on reporting, charging, and convicting an individual. If the underreporting of sexual abuse is an indication, the underreporting and conviction of animal abuse are not nearly representative. Thus, while there is a typology — male, 31-50, five times more likely to commit violent crime — this data is skewed and dated (Luke & Arluke, 1997; Agnew, 1998).

Recognizing and understanding The Link supports preventative efforts to eradicate violence in animal and human (adult and child) service professions. One-third of children who perpetrate animal abuse will go on to later abuse their own children. At least 25% of children whose mothers experience domestic violence have also seen their pets threatened or abused (McDonald et al., 2015). In McDonald’s study (2015), children often reported that the motivation is to control their mothers, again indicating that The Link does have a gender bias. Since pets are often sources of social support for children, this can be traumatic. Alternatively, children may be forced to become complicit in the abuse of the animal.

HB33 clearly specified a cross-reporting mechanism for professionals throughout the state of Ohio. Cross-reporting is ongoing, consistent communication between human service professionals and animal-serving professionals to ensure the health and well-being of all. The legislation specifically references that cross-reporting entails licensed veterinarians, social service professionals, and any other persons licensed as a counselor, social worker, or marriage and family therapist, who must immediately report abuse of a companion animal to an office when that person has knowledge or reasonable cause to suspect such abuse has occurred or is occurring. Simultaneously, law enforcement officers, dog wardens or deputy dog wardens, or humane agents must immediately report abuse of a companion animal to appropriate licensed service professionals with knowledge or reasonable cause to suspect abuse has occurred or is occurring, or if they suspect that a child or older adult resides with the alleged abuser, or if they suspect abuse toward the companion animal may impact the child or older adult (Ohio Revised Code, 2021).

Though this legislation specifies interprofessional engagement, there is no specification of who to call nor a specific or central phone number (e.g., 9-1-1 for emergency services). As such, there are anecdotal stories of calls being placed to a Humane Society but being told there is no space to take in animals who are victims of abuse. Or, calls are placed to child protective services after hours, when abuse tends to occur, but no follow-up is being done. In addition to there being no centralized number to call, there is also no centralized database to capture cases, charges, and convictions. If true, such shortcomings put human and animal lives at risk and impede the very intent of the legislation. In conversation with the advocates who championed this legislation, the intention was to develop a “system of reporting” but fell short of establishing a system to track outcomes about the success and challenges of this policy (V. Deisner, personal communication, September 2024).

Scoping Literature Review#

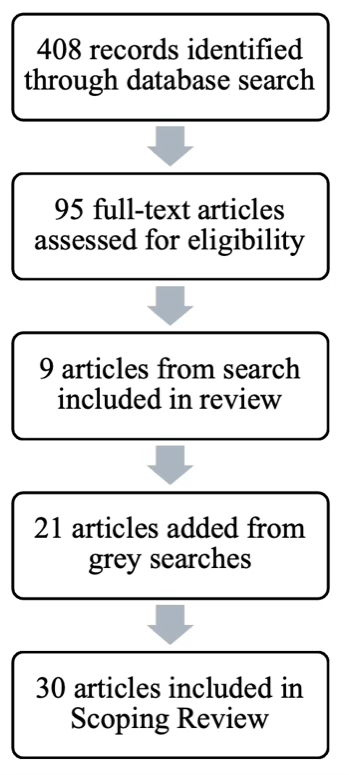

A scoping review of current literature was conducted to contextualize previous research completed on the intersection of interpersonal violence (IPV), child abuse, elder abuse, and animal abuse. Essentially, the search was intended to explore publications on the topic of The Link between forms of IPV and animal cruelty. This research situates the relevance of current legislation as it impacts community practice and the potential magnitude of human and animal abuse being faced in households. Taken together, these keywords assessed the alignment of past research to explore and/or measure The Link and the questions prior research may have raised regarding interpersonal and interspecies relationships.

A literature review was completed in January 2025, using the EbscoHost database. The terms used in this search were: “animal abuse” and “child abuse,” and “animal abuse” and “interpersonal violence.” Studies were considered relevant and included in the analysis if they directly referenced the keywords in the context of The Link.

The keywords “animal abuse” and “child abuse” yielded 168 results, of which 49 were full-text articles. Of the 49 articles, 10 were found to be directly relevant to the research. The keywords “animal abuse” and “interpersonal violence” yielded 240 results, of which 46 were full-text articles. Of the 46 articles, 20 were found to be relevant to the research. From this search, a total of 30 articles were found and read in full. After reading all relevant articles, nine were aligned with the research question and included in the review.

Figure 1. Flow Chart of Articles Included in Scoping Review#

A diagram of a research process AI-generated content may be incorrect.

By using the references in the articles as well as known researchers in the area, additional peer-reviewed papers were identified that were not indicated in the literature search (n=21). This was likely due to the keywords used in the search compared to the keywords identified by the authors. The discrepancy between the articles yielded in this search (n=9) and those found through creative means (n=21) indicates a need for consistency in publication keywords and expanded research in this area. Furthermore, given the extensive research of the individual keywords, the relevant articles (N=30) were minuscule compared to what the researchers aspired to find. The relatively small number of articles discovered throughout the literature review process reflects that there is much to be desired regarding the academic understanding of The Link.

The majority of research was completed in the United States (n=22), with other contributing studies from the United Kingdom (Chan & Wong, 2023; Ireland, 2022; Piper, 2003; Williams, 2022), Canada (Giesbrecht, 2022; Wuerch, 2020), Norway (Muri, 2022), and Australia (Volant, 2008).

Eight articles recognized this relationship of human-animal violence as “The Link” (Flynn, 2011; Muri, 2022; Monsalve, 2017; Poe & Strand, 2022; Sheay, 2020; Jegatheesan, 2020; Tomlinson, 2022; Vincent, 2019). This is significant as it demonstrates how researchers take the connection between IPV and animal abuse as a crucial and serious issue. One paper specifically emphasized the misrepresentation or undefined meaning of abuse, which leads to uncertainty in crucial situations (Piper, 2003). Factors brought up throughout articles, such as parents’ social status, past mental issues, and history of incarceration, create a greater risk of families experiencing companion animal abuse (Flynn, 2011; Ireland, 2022; Muri, K., 2022). Children who grow up in an unstable, abusive, or violent household are more likely to commit violent acts or act out aggressively when they are older (Ascione, 1999; Browne, 2017; Campbell, 2022; Holoyda, 2016; Jegatheesan, 2020; Lockwood, 2016; Longobardi, 2019; McDonald, 2019; Miller, 2001; Mota-Rojas, 2022; Muri, 2022; Trentham, 2018).

The application of The Link framework connects subcategories of violence (i.e., child, adult, elder, and animal) into a cohesive group. Pets are no longer considered property as they once were, but rather are recognized as family members, which impacts the relationship between caregiver and pet. With U.S. homes predominantly relying on women to be caretakers of children, humans, and pets alike, and statistically more often victims of IPV, there is also a gender-based violence component to consider. Pets serve as a comfort in times of violence but also may be the reason a victimized person may choose to stay in a violent situation longer than if they only centered their needs (Giesbrecht, 2022; Jegatheesan, 2020; November, 2024; Vincent, 2019).

Research demonstrates that IPV survivors are concerned for the well-being of their companion animals, which contributes to their distress and can further delay victims from leaving (Fitzgerald, 2022; November, 2024; Giesbrecht, 2022; Volant, 2008). “Studies of women in domestic violence shelters in the United States (US) have documented rates of co-occurrence of IPV and animal abuse ranging from 25% to 86%” (Fitzgerald, 2022; Monsalve, 2017). Experiencing childhood abuse and witnessing other forms of abuse by family members has a direct impact on the timeline of when abuse may occur (Browne, 2017).

One prevalent issue was a significant lack of resources that communities, organizations, and other relevant partners desperately needed but could not obtain. The shortage of services ensuring protection, such as domestic violence shelters allowing companion animals, funds, research, and other unprovided resources, is represented as a common issue and appears in eight unique articles reviewed (McDonald, 2019; Miller, 2001; Newberry, 2017; Patterson-Kane, 2022; Sheay, 2020; Trentham & Williams, 2022; Wuerch, 2020). Recognizing the absence of available resources reinforces the significance of the current research to promote the predominant causes of The Link between animal abuse and IPV and how it can be addressed by community resources. Some communities are taking actionable steps to support survivors and future victims. The Animal Welfare Institute (AWI), for example, indicated that “as data continues to flow in and more law enforcement agencies begin to report, it is becoming ever more possible to determine trends and obtain an accurate assessment of the occurrence of animal cruelty, where it is happening, and the characteristics of the offender” (Beirne & Lynch, 2023).

Research Questions#

The primary research question for this research was to explore the impact of Ohio HB33 on professionals who were named mandatory reporters since its enactment in 2021. This research question explored five areas of knowledge and experience: 1. awareness of legislation and reporting mandate; 2. to whom they report; 3. whether they have reported any instances of suspected Link cases; 4. whether they were notified of follow-up; and 5. identification of challenges in reporting.

Methods#

This IRB-approved study (IRB-FY2024-249) consisted of two phases. The first phase of the research used a researcher-created, confidential digital survey to gather a broad swath of data. Then, the second phase used voluntary focus groups from self-identified respondents to explore the five areas of knowledge and experience questions in further detail. The reporting of the methods herein follows the CHERRIES reporting mechanism (Eysenbach, 2004).

The target population included those currently employed in professions within the state of Ohio who are named as mandatory reporters of suspected animal abuse in HB33. Inclusion criteria for respondents included: 1. Currently employed in a profession identified in HB33; 2. Competent to read and write in English; and 3. Over 18 years of age. The research was conducted over one year, from May 2024 to May 2025, with the survey disseminated in summer 2024 and focus groups held between August and December 2024.

The informed consent for both phases included detailed information regarding the purpose of the study, the length of time to complete the survey, where data were stored and for how long, methods for ensuring confidentiality, and the researcher’s contact information. All data were stored in a password-protected database and analyzed in SPSS.

Survey#

Prior to dissemination, the usability and technical functionality of the survey were tested by the research team. Due to the length of the survey and complex skip patterns, the questions were not randomized, nor was adaptive questioning used. Respondents had the opportunity to review, edit, and skip questions throughout the survey prior to submitting. The survey was considered “open” as individuals could access the survey without login criteria, views were not recorded, and IP addresses were not tracked. Researchers ensured single use by monitoring the informed consent page (which required a name and signature) and the completion rate through regular checks in Qualtrics. The final section of the survey offered respondents the opportunity to provide their name and email if they wanted to be included in the opportunity to receive a gift card, which was randomly selected and emailed.

The survey was distributed via email to over 1,500 professionals in Ohio who were designated as mandatory reporters under HB33. The researcher created the survey, which was housed and distributed via Qualtrics. Distribution was via email to licensing boards and membership-based organizations to distribute to their constituents. The survey was shared on social media (i.e., Facebook, LinkedIn, etc.) and emailed directly to community partners. Of the 1,500 emails sent, 160 professionals completed the survey, resulting in a response rate of approximately 10%.

Frequency distributions were examined for study variables. One-way ANOVAs and chi-square tests were conducted to examine the associations between demographic variables and key aspects such as understanding of The Link, barriers to reporting, and experience with professional training.

Focus Groups#

The second phase of the study was researcher-facilitated virtual focus groups via Zoom. The one-hour focus groups explored the nuances of the research question, allowing the participants to share their personal experiences in more explicit detail than offered in the survey. After completion of the survey, participants were provided the opportunity to leave their names and contact information if they were interested in participating in a focus group. In total, fourteen individuals participated in focus groups between August and October of 2024. Similar to the survey, participants completed an informed consent form before engaging in conversation. The entire conversation was confidential; groups were not recorded. Focus group participants were asked eight guiding questions about training, resources, obstacles to getting help for humans and animals in Ohio, and how to improve protection for humans and animals in Ohio.

Results#

Survey#

The majority of respondents (N=160) were female (78%), followed by males (19%) and non-binary individuals (3%). Approximately two-thirds of the respondents (67%) were aged 35 or older. Occupational distribution showed that nearly half (48%) were involved in human welfare-related professions such as social work and counseling, while 22% were engaged in law and policy, including roles related to domestic violence. Animal welfare and medical roles also constituted significant portions, accounting for 20% and 10%, respectively. The majority of respondents (82%) had at least three years of experience in their current primary occupation. Additionally, a substantial majority (84%) of the participants were classified as mandatory reporters (see Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics (N = 160)#

| Frequency (n=) | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (n = 118) | ||

| Female | 92 | 78.00 |

| Male | 22 | 18.60 |

| Non-binary | 4 | 3.40 |

| Age (n = 118) | ||

| 18-24 years | 2 | 1.70 |

| 25-34 years | 37 | 31.40 |

| 35-44 years | 24 | 20.30 |

| 45-54 years | 24 | 20.30 |

| 55-64 years | 21 | 17.80 |

| 65+ | 10 | 8.50 |

| Primary Occupation (n = 139) | ||

| Human Welfare: APS, LPC, Psy, SW, CPS | 67 | 48.20 |

| Animal Medical: Vet, Vet Tech | 14 | 10.01 |

| Law & policy: Law (all categories), policy, domestic violence | 30 | 21.60 |

| Animal Welfare: Deputy Dog Warden, Dog Warden, Human Agent | 28 | 20.01 |

| Years in Primary Occupation (n = 145) | ||

| 0-2 years | 26 | 17.90 |

| 3-5 years | 20 | 13.80 |

| 6-10 years | 30 | 20.70 |

| 11-15 years | 16 | 11.00 |

| 16 or more years | 53 | 36.60 |

| Are you a mandatory reporter? (n = 131) | ||

| Yes | 110 | 84.00 |

| No | 21 | 16.00 |

Table 2 presents frequency distributions of the Link, barriers to reporting, and experience with professional training. For training on reporting suspected cruelty or neglect of companion animals or humans, approximately 89% of respondents reported having received training in either one or both types of cruelty or neglect. Conversely, 11% indicated that they had not received any training related to animal or human cruelty and neglect. Slightly more than half of the respondents (53%) reported that they have seen an increase in human and/or animal abuse over the last three years. Additionally, a significant number of respondents (84%) have encountered situations where they suspected human or animal abuse. In terms of abuse types, animal cruelty and neglect were most frequently suspected (55%), followed by child cruelty and neglect (27%) and spousal cruelty and neglect (14%). The most prevalent reasons for suspecting human or animal abuse include the behavior of people (54%), people who reported cruelty and neglect (61%), and the physical appearance of animals (53%).

Table 2. Frequencies of the Link, Barriers to Reporting, and Experience with Professional Training#

| Frequency (n = ) | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Received any training on how to report suspected cruelty or neglect of companion animals or humans? (n = 141) | ||

| Yes, human cruelty & neglect | 33 | 23.40 |

| Yes, animal cruelty & neglect | 21 | 14.90 |

| Yes, both human and animal cruelty & neglect | 71 | 50.40 |

| No training | 16 | 11.30 |

| In the last three years, I have seen an increase in human and/or animal abuse (n = 144) | ||

| Yes | 76 | 52.80 |

| No | 52 | 36.10 |

| I don’t know | 16 | 11.10 |

| In the last three years, I have been in a situation where I suspected human or animal abuse (n = 137) | ||

| Yes | 115 | 83.90 |

| No | 22 | 16.10 |

| Yes, within the last three years, I have been in a situation(s) where I suspected human or animal abuse with (n = 114) | ||

| Animal cruelty & neglect | 63 | 55.30 |

| Child cruelty & neglect | 31 | 27.20 |

| Elder cruelty & neglect | 4 | 3.50 |

| Spousal cruelty & neglect | 16 | 14.00 |

| What made you suspect human or animal abuse (n = 114) | ||

| The behavior of people | 62 | 54.40 |

| Physical appearance of people | 39 | 34.20 |

| Person reported cruelty & neglect | 69 | 60.50 |

| Behavior of an animal | 38 | 33.30 |

| Physical appearance of an animal | 60 | 52.60 |

| Other | 4 | 3.50 |

| Who did you report the abuse to? (n = 99) | ||

| Humane agency | 43 | 43.40 |

| Law enforcement | 34 | 34.30 |

| Social work agency | 51 | 51.50 |

| Direct supervisor | 17 | 17.20 |

| The Courts | 14 | 14.10 |

| Other | 14 | 14.10 |

| What was the result of your report of abuse? (n = 98) | ||

| A police report was filed | 25 | 25.50 |

| Criminal charges filed | 21 | 21.40 |

| The abuser was convicted of cruelty & neglect | 13 | 13.30 |

| Removal of a child | 13 | 13.30 |

| Removal of partner | 4 | 4.10 |

| Removal of an elderly individual | 0 | 0.00 |

| Removal of an animal | 23 | 23.50 |

| Nothing was done | 22 | 22.40 |

| Other | 8 | 8.20 |

| Don’t know | 30 | 30.60 |

| Do you think that others who are mandatory reporters for animal abuse in Ohio are (n = 88) | ||

| Aware that they are a mandatory reporter of animal cruelty & neglect | 73 | 83.00 |

| Aware and know what to do if they suspect animal cruelty & | 33 | 37.50 |

| neglect | ||

| Aware of how to report animal cruelty & neglect | 33 | 37.50 |

| Consistent in reporting of suspected animal abuse | 19 | 21.60 |

| Consistent in responding to call(s) for suspected abuse (i.e., check all individuals and animals in the home) | 26 | 29.50 |

| Do you think that Ohio House Bill 33 has been effective at increasing protection for humans and animals in Ohio? (n = 110) | ||

| Yes, for animals | 19 | 17.30 |

| Yes, for humans | 14 | 12.70 |

| Yes, for humans and animals | 52 | 47.30 |

| Not for humans nor animals | 25 | 22.70 |

| Obstacles to increasing protection for humans and animals in Ohio (n = 101) | ||

| I don’t know if I am a mandatory reporter | 9 | 8.90 |

| I don’t know how to recognize human cruelty & neglect | 7 | 6.90 |

| I don’t know how to recognize animal cruelty & neglect | 8 | 7.90 |

| I don’t know who to call | 18 | 17.80 |

| If I call, others don’t care | 24 | 23.80 |

| I don’t know what to look for | 3 | 3.00 |

| There are not enough people/agencies to help | 60 | 59.40 |

| Other | 38 | 37.60 |

| On a scale of 1 to 10, how much do you think human and animal cruelty and neglect are linked or related to each other (n = 117) (Mean/SD) | 8.54 (2.02) |

Reports of abuse were predominantly directed towards social work agencies (52%), humane agencies (43%), and law enforcement (34%). The outcomes following the reports of abuse reveal a mixed effectiveness of the response systems. While police reports were filed in 26% of cases, criminal charges were filed in 21%, and animals were removed in 24% of cases, a substantial proportion (22%) saw no action taken, and there was a high level of uncertainty among respondents about the outcomes (31% didn’t know the result).

A substantial majority (83%) of respondents reported that others who were mandatory reporters in Ohio knew that they were mandatory reporters for animal cruelty and neglect. However, the respondents perceived that only 38% of the mandatory reporters in Ohio were aware of what specifically to do if they suspected animal cruelty and neglect and knew how to properly report it. Additionally, only 21.6% of respondents thought that the mandatory reporters in Ohio were consistent in reporting suspected animal abuse and 29.5% in checking all individuals and animals in the home when responding to calls.

Regarding the effectiveness of HB33 in increasing protection for humans and animals, slightly less than half of the respondents (47%) reported that the policy had been effective for both humans and animals. Smaller proportions of respondents saw its effectiveness as limited to either animals (17%) or humans (13%), and 23% did not believe it has been effective for either group. Among the obstacles to increasing protection for humans and animals in Ohio, the most prominent obstacle reported is the lack of sufficient resources or agencies to help (59%).

A significant concern (24%) also existed around the efficacy of reporting, with respondents feeling that their reports of cruelty or neglect do not result in adequate care or action. Additionally, knowledge gaps are also notable, with respondents unsure of their roles as mandatory reporters (9%), how to recognize signs of cruelty (7% for humans, 8% for animals), and who to contact (18%). Finally, respondents generally perceive a strong link between human and animal cruelty and neglect, with an average score of 8.5 (Range 1-10, SD = 2.02).

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics of demographic factors among the four groups differentiated by their training experiences. There were significant differences in the type of primary occupation by the four groups of training experience. Individuals in human welfare professions (such as adult protective services, mental health counseling, social work, and child protective services) are higher in receiving training on both human and animal cruelty and neglect (p < .001). Being a mandatory reporter was significantly lower among those who had not received any training on cruelty and neglect compared to the remaining three groups with training experiences (p < .01).

Awareness of encountering suspected abuse in the last three years was lower among untrained individuals compared to those trained in any capacity (p < .001). Moreover, the type of suspected abuse also shows significant variations by the four groups of training experience, with animal cruelty and neglect being the most frequently suspected (p < .01). The capability to recognize abuse based on the physical appearance of animals also shows significant differences based on training; those without training are lower in reporting abuse based on these visual cues (p < .001).

Reporting practices also show significant differences; individuals with no training were lower in reporting abuse to human agencies compared to their trained counterparts (p < .05). Outcomes following these reports, such as police reports being filed (p < .05), abusers being convicted (p < .05), and animals being removed (p < .01), also vary significantly with training experience. Lastly, awareness among professionals that they are mandatory reporters of animal cruelty and neglect in Ohio was significantly lower in the untrained group compared to those who received training (p < .05). Similarly, the understanding of the connection between human and animal cruelty and neglect was significantly higher among those trained specifically in animal cruelty and neglect (p < .001).

Focus Groups#

Four focus groups were conducted between August and October of 2024. Focus group participants consisted of dog wardens, deputy dog wardens, rescue and adoption center employees, humane agents, social workers, veterinarians, academics, and policy workers (n = 15). Demographic information of this sample is not provided as it is small in size and could easily lead to the identification of persons, which would negatively impact the professional relationship and void the informed consent agreement. Participants were asked the following eight guided questions, with additional follow-up questions as needed, and one open-ended question at the end of the focus group session:

Please think about the last time that you saw, suspected, reported, or responded to a call for human and animal abuse. Can you tell me a bit about those situations?

Have you received any prior training on how to manage these situations?

Can you think of anything that would have helped you respond better to the situation?

What did you feel were the biggest obstacles in getting help with the situation?

At that time, was there any place you could go to overcome these obstacles?

Based on your experiences, what do you think can be done to increase protection for humans and animals in Ohio?

Are you familiar with the concept of the Link?

Have you ever reported an instance of the Link?

Participant responses are reported in the aggregate below. In totality, the respondents were supportive of and complementary to the quantitative findings.

Almost all focus group participants reported that they had experience with The Link, whether or not by use of the exact terminology. Given their professions, some stated that they witness human and animal violence daily. Participants named key “red flags” that they identify as potential indicators of interspecies violence: lack of hygiene of children, adults, or the elderly; or environmental concerns, such as dirty homes, debris outside the home such as car pieces all over, or unkempt grass and landscaping. Participants expressed frustration because even when they witnessed these red flags, there were few resources for them to call for help. Supervisors or outside agencies, to whom HB33 mandated as cross-reporting partners, did not share their concern or would not help. The participants shared conflicted feelings of passion for their work along with helplessness to effect change.

Participants expressed a collective sense of isolation in their work. Some expressed not knowing they were considered mandatory reporters until they were contacted by this research team. Others stated that while they knew they were mandatory reporters, they did not know whom to call for support. Most importantly, it was unanimous among participants that even if they called and received support (e.g., a law enforcement officer starting a case file), there was no follow-through or sharing of reporting back to the person who placed the initial report. This lack of communication is concerning because HB33 is grounded in the empirical framework that early, multisystemic intervention can save lives when used effectively, whether it is a human or an animal life.

Participants shared successes in their work, such as efforts in specific counties within Ohio that address this work as a multidisciplinary team. As a team, when there is a notification of an instance of suspected neglect or abuse (human or animal), multiple members of the team will arrive on the scene to offer either support or removal. Team members included humane agents, social workers, specially trained law enforcement, and related agency professionals (i.e., adult or child protective services). These individuals would combine their resources, offer education (e.g., food, medical care), and oftentimes, the removal of a victim.

Participants almost unanimously had not received training regarding The Link (n=13), even as mandatory reporters. Most individuals received training within their disciplinary silo. For example, a social worker would be trained in what to look for in suspected child abuse, or a veterinarian may have taken voluntary courses to learn about what to look for, but very few participants (n=2) noted that it was required for them to attend or complete those trainings. Those reporting that it was required were primarily humane agents, who reported that they were well-versed in looking for animal abuse but not for human abuse.

Discussion#

The goal of Ohio HB33 was to help protect both animals and humans. The bill added individuals as mandatory reporters, and those mandatory reporters were to report anytime they suspected animal abuse or neglect while in a work capacity. Because there is a statistical link between violence among humans and animals, any time a mandatory reporter entered a home or suspected abuse at, for example, a veterinary clinic, by reporting this suspected abuse, they would be able to provide help to individuals and more than likely save lives. Additionally, multisystemic reporting would address the issue of individuals who inherently have a propensity for violence towards living and sentient beings. This study aimed to examine if this goal was met, identify where there are strengths and room for improvement, and then provide recommendations and suggestions for policy improvement. Based on the findings, there are three primary needs to enhance the current policy: education, training, and policy advancement.

Education#

First, both quantitative and qualitative analyses evince that widespread education on The Link must be offered. Though the majority of the participants shared that they had not heard the term or concept of “The Link,” when a definition was provided, they confirmed that they witnessed it often or every day. These statements evince that there is a crucial need for educating others on this important link between interspecies violence, sharing the statistical and relational propensity for the inherent violence of some individuals to not discriminate toward whom they harm, and approaching said violence from a multi-systemic, teamwork-based approach. Understanding that there is a solidified statistical relationship and academic concept that designates a link between human and animal violence is crucial to a working population that is so desperately and passionately trying to get help and resources.

Educating mandatory reporters is critical for them to understand what they are looking for, who to report to, why it is so important to report, and also to provide support for what they already know: that an entire household is at risk if aid or removal of danger is not provided. Education must extend not only to supervisors and administrators in the fields of animal welfare, social and adult protective services, and anyone who works in the field of animal care, but also to county administrators, city managers, and those who are responsible for determining what agencies provide resources. This must also include those who work in the court system.

Many participants noted distress when they did not receive follow-up on a case they had reported, courts not taking this issue seriously, and individuals either not being charged with cruelty and neglect or being charged and then having those charges dropped. Education is one way in which the risk to both animals and humans may be exposed, but it also must be widespread and target the appropriate audience. This reiterates the importance of addressing this form of violence from multiple perspectives and with multiple agencies as a systemic force to address not only the current situation but the propensity and opportunity for later violence.

Training#

Second, there is clearly a need and desire for training on The Link. At present, there is a lack of clarity for mandatory reporters about whom to report to, what cross-reporting is (hence, the importance of training), and the measurable impact of the cross-reporting mechanism. As this is central to HB33, it is evident that the policy has positive intentions but a lack of efficacy and efficiency in practice due to the lack of training at the time of implementation.

This study has shown that individuals who go into homes for welfare checks or who respond to calls for abuse and neglect sometimes learn on the job. In one case, a focus group participant reported that when they started work, they were given the keys to the office and told, “Good luck.” They were not trained, did not have to complete any statewide or mandatory training, and were unsure of whom to report abuse to when and if they saw it. There is minimal training on abuse and survivors in law enforcement training and reportedly none in the veterinary field that is required (Ohio Veterinary Medical Association, 2020, 2023). The findings herein demonstrate that mandatory reporters want and are asking to be trained.

Mandatory training should be extended to attorneys, court officials, city and county administration, law enforcement (i.e., police), emergency medical services (i.e., EMS and firefighters), veterinarians and veterinary technicians, and child and adult protective supervision employees. Training must include the academics behind The Link (re: education) but must also focus on the practical application, such as what to look for, whom to call, how to respond, and how to determine the level of potential danger. Based on the quantitative and qualitative findings, those who were trained in The Link expressed higher levels of professional comfort identifying instances of The Link, knowing how to appropriately respond, and, of those who had training, many had formed community coalitions and response teams.

Policy Advancement#

Third, while HB33 was a tremendous advancement for the State of Ohio, it is important to revisit and evaluate all policies and form a policy focused on best practices. HB33 included mandatory reporters such as social workers and veterinarians but failed to include other categories of individuals who work in client/community homes or are privy to information that may lead to a disclosure of neglect or abuse. For example, home health aides, occupational therapists, and guardians ad litem. Guardians ad litem go into homes and are tasked with writing a report to the court that notes what is in the best interest of a child (Ohio Revised Code Section 2151.281, 2025). The “best interest” standard is a legal standard, and a guardian ad litem is to walk through a home and interview all involved parties. However, at present, they are not required to consider the conditions of animals. If a guardian ad litem were trained to account for pets as family members, they might request to view and interact (species-specific and appropriate) with the pet in the home as well. If they found malnourishment, neglect, or abuse of the animal, then the guardian ad litem should note that in the court report and immediately report the issue to the appropriate agency. The court must consider the information provided when determining what is in the best interest of the child. Thus, HB33 must be reviewed to consider additional categories of occupations and/or individuals who should be added as mandatory reporters.

Upon its passage, HB33 was not disseminated to the general public or to the mandatory reporters themselves. The intention of the policy was to make sure that all mandatory reporters reported animal abuse. However, if a dog warden was not made aware that they were a mandatory reporter, or if those who are named mandatory reporters for child abuse were unaware of HB33, there would be no follow-through of cross-reporting. There is a profound difference between not knowing how to communicate and not communicating efficiently. As currently written, HB33 lacks the implementation and enforcement that it intended to have. The general public and all mandatory reporters must be made aware of the existence and requirement to report in order for the intention of the policy to match its implementation.

Perhaps the greatest drawback of House Bill 33 in Ohio was that funding and research to implement the Bill and carry out its intention have not yet realized their full potential. Those who hold the purse strings and dispense grants and annual funding must get on board with this Bill. They must provide funding for the training of mandatory reporters and the courts, provide space and resources for abuse victims to be placed, and they must provide protection for those who report. Individuals who have a propensity for violence to harm animals and humans are highly dangerous. Administrators, city officials, and court staff need to be part of this effort to protect their community and truly innocent victims from these violent individuals before it is too late. Up to this point, they have not.

Recommendations#

- As currently written, HB33 lacks the implementation and enforcement that it intended to have. The general public and all mandatory reporters must be made aware of the existence and requirement to report in order for the intention of the policy to match its implementation.

- Implementation of HB33 is contingent on all mandatory reporters (in Ohio) completing a required annual training. The training should be offered in person (i.e., at statewide professional conferences) and online, with approved continuing education credits.

- Mandatory reporters need to have a central phone number to call for the cross-reporting requirement. Those who answer must be responsible for connecting professionals to their colleagues (i.e., a social worker to a humane agent).

- Data collected from calls needs to be integrated into a statewide database (i.e., Ohio Incident-Based Reporting System, OIBRS), a voluntary database of crime statistics used by Ohio law enforcement, and/or a national database (i.e., National Incident-Based Reporting System, NIBRS), the “national standard for law enforcement crime data reporting in the United States” (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2023).

- The policy must be reviewed to consider additional categories of occupations and/or individuals who should be added as mandatory reporters, as many are currently absent from the current iteration.

- The policy needs to have a clear message regarding the importance of addressing interpersonal and interspecies violence by multiple professions/agencies as a systemic force. One clear message will aid the community in a clear understanding of the intention of the policy.

- The state is encouraged to financially invest in the recommended training, central phone number, and database management.

Limitations#

While this research was novel and necessary, there are limitations that will be addressed in future efforts. A ten-percent response rate is appropriate for survey research; however, the researchers would like to have a larger sample that is representative of the relevant professions. Also pertaining to the survey, the researchers are aware that the survey was long; respondents were informed that it could take about 15-20 minutes to complete. An incentive was provided because of the length and sensitive nature of the survey, both of which were disclosed in the informed consent. However, the length of the survey may have deterred some respondents.

Though the participants chose to attend the focus group(s) virtually, the researchers aspired to have the conversations in person and are curious if an in-person conversation would have shifted any responses. The focus groups were not recorded, which may have resulted in some lost data by virtue of listening and note-taking without the opportunity to listen back.

Future Research#

In tandem with pursuing publication of the research, findings will be shared with all community members who participated in this study. Future research efforts should continue to engage community members in conversation and consider participatory action research as a model for future work. The researchers intend to create an online, asynchronous training module for professionals to access individualized learning, as well as for organizations to integrate into their professional onboarding of new hires and training of staff. Evaluation of this effort will support continuous improvement.

House Bill 33 provides a strong framework for the advancement of the protection of humans and animals; its passage was nothing short of monumental. Continued evaluation of the policy and its implementation must be a consistent process. Thus, updates to HB33 must be made where and when possible. The continued formation of a best practices model will serve as a framework for additional states and countries to add similar policies to their legislation. Future research should seek to develop an updated typology of offenders, victims, and survivors. Similarly, consistent research that evaluates how policy is implemented and actualized in practice serves to improve the intention of policy and the efforts of community practice.

Conclusion#

Ohio House Bill 33 was passed with the intention of addressing The Link by requiring mandatory reporters to report suspected animal abuse through a cross-reporting mechanism. The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of House Bill 33. This research explored five areas of knowledge and experience: 1. awareness of legislation and reporting mandate; 2. to whom they report; 3. if they have reported any instances of suspected Link cases; 4. whether they were notified of follow-up; and 5. identification of challenges of reporting.

Through the dissemination of an online, confidential survey to mandatory reporters and the facilitation of focus groups, strengths and opportunities for improvement were identified. As a strength, this policy is unique and novel in its approach to developing interdisciplinary professional teams to explicitly address interspecies and interpersonal violence. However, there is a lack of communication about who is a mandatory reporter, while others also did not know about HB33. Education in the concept of The Link needs to be increased throughout the state, including explicit training on how to recognize and report suspected abuse. Finally, the state is encouraged to invest in resources to support professionals who report by creating a centralized phone number and database, as well as encouraging follow-through conversations to increase trust amongst professionals. HB33 has been a positive shift in Ohio, though the potential is great to increase impact.

While Ohio works to refine its policy and practice to address The Link, it also serves as a novel case study for other communities. Opportunities to apply this research to other communities are evident through the five identified areas of knowledge and experience. Learning explicitly about The Link supports professionals’ knowledge and skills to identify suspected abuse or maltreatment. In doing so, professionals are able to be more effective in their roles. Knowing whom to report suspected human or animal violence to, even when reporting is not mandated, may be a life-saving action. Human service and animal welfare professionals are encouraged to become aware of and raise awareness of legislation and reporting mandates.

Experience of reporting instances of The Link has been met with both positive and negative affirmations. In some cases, professionals identified feeling as though they were better able to support their clients by understanding the family unit, inclusive of pets; other times, professionals shared frustration because of the lack of system-level support to notify other professionals or receive follow-up that their report made a difference for their client. The frustration is significant because a consistent lack of acknowledgement, especially in challenging cases, can be a factor in burnout. These areas of knowledge and experience can be experienced in a linear and iterative manner based on individual experiences and needs. By acknowledging these as opportunities, other communities may be able to establish supportive policies, community practices, and professional role expectations that support engagement in the identification of suspected link activities.

Bibliography#

Agnew, R. (1998). The causes of animal abuse: A social-psychological analysis. Theoretical criminology, 2 (2), 177–209.

American Pet Products Survey (2022) Pet Industry Market Size, Trends & Ownership Statistics. Retrieved from: https://www.americanpetproducts.org/press_industrytrends.asp.

Arkow, P. (2023) The National Link Coalition. Retrieved from: https://nationallinkcoalition.org/.

Ascione, F. R. (1999). The abuse of animals and human interpersonal violence: Making the connection. Child abuse, domestic violence, and animal abuse: Linking the circles of compassion for prevention and intervention, 50–61.

Ascione, F.R., & Lockwood, R. (2001). Cruelty to animals: Changing psychological, social, and legislative perspectives. In D.J. Salem & A.N. Rowan (Eds.), The state of the animals 2001 (pp. 39-53). Washington, DC: Humane Society Press.

American Society for the Protection of Cruelty to Animals (2022) Research. Retrieved from: aspcapro.org/left-navigation/research.

Animal Welfare Institute (2023) Animal Welfare Institute. Retrieved from: https://awionline.org/.

Beirne, P., & Lynch, M. J. (2023). On the Geometry of Speciesist Policing: The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Animal Cruelty Data. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 12 (2), 137–149.

Browne, J. A., Hensley, C., & McGuffee, K. M. (2017). Does witnessing animal cruelty and being abused during childhood predict the initial age and recurrence of committing childhood animal cruelty? International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 61 (16), 1850–1865. URL: https://doi-org.proxy.ulib.csuohio.edu/10.1177/0306624X16644806.

Bureau of Justice Statistics (2023) National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS). Retrieved from: https://bjs.ojp.gov/national-incident-based-reporting-system-nibrs.

Campbell, A. M. (2022). The intertwined well-being of children and non-human animals: An analysis of animal control reports involving children. Social Sciences, 11 (2), 46.

Chan, H. C. O., & Wong, R. W. (Eds.). (2023). Animal Abuse and Interpersonal Violence: A Psycho-Criminological Understanding. John Wiley & Sons.

Counselor, Social Worker, Marriage and Family Therapist Licensure Board (CSWMFT) (2023) For the Public. Retrieved from: https://tinyurl.com/2cmdcxee.

Eysenbach G. (2004). Improving the quality of Web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). Journal of medical Internet research, 6 (3), e34. URL: https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34.

Fitzgerald, A. J., Barrett, B. J., Gray, A., & Cheung, C. H. (2022). The connection between animal abuse, emotional abuse, and financial abuse in intimate relationships: Evidence from a nationally representative sample of the general public. Journal of interpersonal violence, 37 (5–6), 2331–2353.

Flynn, C. P. (2011). Examining the links between animal abuse and human violence. Crime, law and social change, 55, 453–468.

Giesbrecht, C. J. (2022). Intimate partner violence, animal maltreatment, and concern for animal safekeeping: A survey of survivors who owned pets and livestock. Violence against women, 28 (10), 2334–2358.

Holoyda, B. J., & Newman, W. J. (2016). Childhood animal cruelty, bestiality, and the link to adult interpersonal violence. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 47, 129–135. URL: https://doi-org.proxy.ulib.csuohio.edu/10.1016/j.ijlp.2016.02.017.

Ireland, J. L., Birch, P., Lewis, M., Mian, U., & Ireland, C. A. (2022). Animal abuse proclivity among women: Exploring callousness, sadism, and psychopathy traits. Anthrozoös, 35 (1), 37–53.

Jegatheesan, B., Enders-Slegers, M.-J., Ormerod, E., & Boyden, P. (2020). Understanding the Link between Animal Cruelty and Family Violence: The Bioecological Systems Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17 (9). URL: https://doi-org.proxy.ulib.csuohio.edu/10.3390/ijerph17093116.

Lockwood, R., & Arkow, P. (2016). Animal abuse and interpersonal violence: The cruelty connection and its implications for veterinary pathology. Veterinary Pathology, 53 (5), 910–918.

Longobardi, C., & Badenes-Ribera, L. (2019). The relationship between animal cruelty in children and adolescent and interpersonal violence: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 46, 201–211. URL: https://doi-org.proxy.ulib.csuohio.edu/10.1016/j.avb.2018.09.001.

Luke, C., & Arluke, A. (1997). Physical cruelty toward animals in Massachusetts, 1975-1996. Society & Animals, 5 (3), 195–204.

McDonald, S. E., Collins, E. A., Nicotera, N., Hageman, T. O., Ascione, F. R., Williams, J. H., & Graham-Bermann, S. A. (2015). Children’s experiences of companion animal maltreatment in households characterized by intimate partner violence. Child abuse & neglect, 50, 116–127.

McDonald, S. E., Collins, E. A., Maternick, A., Nicotera, N., Graham-Bermann, S., Ascione, F. R., & Williams, J. H. (2019). Intimate partner violence survivors’ reports of their children’s exposure to companion animal maltreatment: A qualitative study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34 (13), 2627–2652. URL: https://doi-org.proxy.ulib.csuohio.edu/10.1177/0886260516689775.

Miller, C. (2001). Childhood animal cruelty and interpersonal violence. Clinical Psychology Review, 21 (5), 735–749.

Monsalve, S., Ferreira, F., & Garcia, R. (2017). The connection between animal abuse and interpersonal violence: A review from the veterinary perspective. Research in veterinary science, 114, 18–26.

Mota-Rojas, D., Monsalve, S., Lezama-García, K., Mora-Medina, P., Domínguez-Oliva, A., Ramírez-Necoechea, R., & Garcia, R. D. C. M. (2022). Animal abuse as an indicator of domestic violence: One health, one welfare approach. Animals, 12 (8), 977.

Muri, K., Augusti, E. M., Bjørnholt, M., & Hafstad, G. S. (2022). Childhood experiences of companion animal abuse and its co-occurrence with domestic abuse: evidence from a national youth survey in Norway. Journal of interpersonal violence, 37 (23–24), NP22627–NP22646.

Newberry, M. (2017). Pets in danger: Exploring the link between domestic violence and animal abuse. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 34, 273–281.

November, R. (2024). Protection for pets and people: The critical need for increased federal funding for pet‐friendly domestic violence services. Family Court Review, 62 (1), 243–256. URL: https://doi-org.proxy.ulib.csuohio.edu/10.1111/fcre.12776.

Ohio Revised Code (2021) Section 1717.01. Humane society definitions. Retrieved from: https://codes.ohio.gov/ohio-revised-code/section-1717.01.

Ohio Revised Code (2025) Section 2151.281. Guardian ad Litem. Retrieved from: https://codes.ohio.gov/ohio-revised-code/section-2151.281.

Ohio Veterinary Medical Association (2020) Animal Abuse Recognition and Reporting. Provided by the Ohio Veterinary Medical Association Animal Abuse Recognition & Reporting Task Force. Available at www.ohiovma.org/abuse.

Ohio Veterinary Medical Association (2023) Resources. Retrieved from: https://www.ohiovma.org/.

Patterson-Kane, E. G., Kogan, L. R., Gupta, M. E., Touroo, R., Niestat, L. N., & Kennedy-Benson, A. (2022). Veterinary needs for animal cruelty recognition and response in the United States center on training and workplace policies. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 260 (14), 1853–1861.

Piper, H. (2003). The linkage of animal abuse with interpersonal violence: A sheep in wolf’s clothing? Journal of Social Work, 3 (2), 161–177.

Poe, B. A., & Strand, E. B. (2022). History of veterinary social work. In The Comprehensive Guide to Interdisciplinary Veterinary Social Work (pp. 13–43). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Robinson, C., & Clausen, V. (2021). The link between animal cruelty and human violence. FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, 10. Retrieved from: URL: https://tinyurl.com/yemovp9d.

Sheay, E. (2020). People Who Hurt Animals Don’t Stop with Animals: The Use of Cross-Checking Domestic Violence and Animal Abuse Registries in New Jersey to Protect the Vulnerable. Animal Law Review, 26 (2), 445–473.

Tomlinson, C. A., Murphy, J. L., Matijczak, A., Califano, A., Santos, J., & McDonald, S. E. (2022). The Link between Family Violence and Animal Cruelty: A Scoping Review. Social Sciences, 11 (11), 514.

Trentham, C. E., Hensley, C., & Policastro, C. (2018). Recurrent childhood animal cruelty and its link to recurrent adult interpersonal violence. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 62 (8), 2345–2356. URL: https://doi-org.proxy.ulib.csuohio.edu/10.1177/0306624X17720175.

Vincent, A., McDonald, S., Poe, B., & Deisner, V. (2019). The Link between interpersonal violence and animal abuse. Society Register, 3 (3), 83–101.

Volant, A. M., Johnson, J. A., Gullone, E., & Coleman, G. J. (2008). The relationship between domestic violence and animal abuse: An Australian study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23 (9), 1277–1295.

Williams, J. M., Wauthier, L., Scottish SPCA, & Knoll, M. (2022). Veterinarians’ experiences of treating cases of animal abuse: An online questionnaire study. Veterinary record, 191 (11).

Wood, L., Martin, K., Christian, H., Nathan, A., Lauritsen, C., Houghton, S., … & McCune, S. (2015). The pet factor-companion animals as a conduit for getting to know people, friendship formation and social support. PloS one, 10 (4), e0122085.

Wuerch, M. A., Giesbrecht, C. J., Price, J. A. B., Knutson, T., & Wach, F. (2020). Examining the relationship between intimate partner violence and concern for animal care and safekeeping. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35 (9–10), 1866–1887. URL: https://doi-org.proxy.ulib.csuohio.edu/10.1177/0886260517700618.

Соединяя политику и практику: изучение осведомлённости специалистов, барьеров и опыта в сообщениях о «Связи» между насилием над людьми и жестоким обращением с животными#

Авива Винсент, Юнис Ли, Алана Ван Ганди, Лорен Касуэлл, Линда Квинн

Аннотация. Цель исследования: «The Link» (Связь) представляет собой признанный поведенческий феномен, согласно которому жестокое обращение с домашними животными может служить индикатором межличностного насилия, насилия над детьми или пожилыми людьми. Закон штата Огайо № 33 (HB33), принятый в 2021 году, ввёл обязанность специалистов сообщать о подозрениях на жестокое обращение с животными. В данном исследовании этот Закон используется для оценки эффективности подобных законодательных инициатив.

Гипотеза: В представленном пилотном исследовании анализируются цели и предполагаемое воздействие закона HB33 с учётом демографических переменных (возраст, пол, род профессиональной деятельности), уровня осведомлённости о «Связи», существующих барьеров информирования о случаях жестокости и наличия профессиональной подготовки.

Методы: Конфиденциальное анкетирование было направлено более чем 1500 специалистам, обозначенным в HB33 как лица, обязанные информировать о соответствующих случаях (mandatory reporters). Получено 160 ответов. Для анализа взаимосвязей между демографическими характеристиками и ключевыми переменными использовались однофакторный дисперсионный анализ (ANOVA), χ²-критерий и t-критерий Стьюдента для независимых выборок. По завершении опроса респонденты были приглашены к участию в фокус-группах (N=14).

Результаты: Большинство участников опроса составили женщины (78%) в возрасте от 35 лет и старше. Почти половина работала в сфере социальной защиты человека, в то время как около 20% были задействованы в защите животных. Осведомлённость о «Связи» была ниже у специалистов в сфере социальной работы по сравнению с теми, кто работает с животными (p < 0,01). Основания для подозрений о жестоком обращении также варьировались по секторам: работники социальной сферы чаще основывали свои подозрения на поведении или внешнем виде людей, тогда как специалисты в области защиты животных — на поведенческих и физических признаках у самих животных (p < 0,01).

Выводы: Полученные данные подчёркивают тесную взаимосвязь между насилием над людьми и жестоким обращением с животными, что требует применения межсистемного (многоуровневого) подхода. В числе рекомендаций — уточнение формулировки обязанностей лиц, которым HB33 предписывает сообщать о случаях жестокости, выделение финансирования на обязательную подготовку специалистов и создание централизованной системы учёта и передачи информации. Делается вывод о том, что, несмотря на выявленные недостатки, HB33 может служить моделью для внедрения аналогичных инициатив в других штатах.

Значение для общественной практики: Это инновационное исследование демонстрирует существующее противоречие между намерениями законодательства и практикой его реализации. Хотя HB33 является необходимым и добросовестно сформулированным нормативным актом, специалисты, ответственные за сообщение о случаях жестокости по отношению к животным, не могут эффективно исполнять свои обязанности без соответствующего информирования и обучения. Законодательные инициативы, подобные HB33, будут значительно более эффективны при условии наличия финансовой поддержки их внедрения, регулярного обучения лиц, реализующих предусмотренные им меры, и систем отслеживания данных для постоянной корректировки. Более того, такие законодательные инициативы действительно предоставляют специалистам на местах, в сообществах, возможность спасать жизни — как человеческие, так и животных, — что и является изначальной целью данной политики.

Ключевые слова: зооправо, зооэтика, социальная политика, “The Link”, жестокое обращение с животными, межличностная жестокость, межвидовая жестокость, обязанность информировать, межведомственное информирование, комбинированный метод исследования, количественные методы, качественные методы.

Table 3. Results of Descriptive Statistics of Demographic Characteristics by Training Experiences#

| Total | Training on Human Cruelty & Neglect (n = 33) | Training on Animal Cruelty & Neglect (n = 21) | Training on Both Human and Animal Cruelty & Neglect (n = 71) | No Training (n = 16) | Chi-square / F value | p value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (%) or Mean (SD) | ||||||||||||

| Gender (n = 118) | ||||||||||||

| Female | 92.00 | 78.00 | 19.00 | 16.10 | 15.00 | 12.70 | 50.00 | 42.40 | 8.00 | 6.80 | 3.58 | 0.73 |

| Male | 22.00 | 18.60 | 5.00 | 4.20 | 4.00 | 3.40 | 9.00 | 7.60 | 4.00 | 3.40 | ||

| Non-binary | 4.00 | 3.40 | 1.00 | 0.80 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 1.70 | 1.00 | 0.80 | ||

| Age (n = 118) | ||||||||||||

| 18-24 years | 2.00 | 1.70 | 1.00 | 0.80 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.80 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 8.95 | 0.88 |

| 25-34 years | 37.00 | 31.40 | 9.00 | 7.60 | 8.00 | 6.80 | 15.00 | 12.70 | 5.00 | 4.20 | ||

| 35-44 years | 24.00 | 20.30 | 6.00 | 5.10 | 5.00 | 4.20 | 11.00 | 9.30 | 2.00 | 1.70 | ||

| 45-54 years | 24.00 | 20.30 | 4.00 | 3.40 | 3.00 | 2.50 | 15.00 | 12.70 | 2.00 | 1.70 | ||

| 55-64 years | 21.00 | 17.80 | 4.00 | 3.40 | 3.00 | 2.50 | 11.00 | 9.30 | 3.00 | 2.50 | ||

| 65+ | 10.00 | 8.50 | 1.00 | 0.80 | 1.00 | 0.80 | 8.00 | 6.80 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| Primary Occupation (n = 139) | ||||||||||||

| Human Welfare: APS, LPC, Psy, SW, CPS | 67.00 | 48.20 | 20.00 | 15.40 | 1.00 | 0.80 | 36.00 | 27.70 | 6.00 | 4.60 | 56.55 | <.001 |

| Animal Medical: Vet, Vet Tech | 14.00 | 10.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 8.00 | 6.20 | 4.00 | 3.10 | 1.00 | 0.80 | ||

| Law & policy: Law (all categories), policy, domestic violence | 30.00 | 21.60 | 12.00 | 9.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 14.00 | 10.80 | 4.00 | 3.10 | ||

| Animal Welfare: Deputy Dog Warden, Dog Warden, Human Agent | 28.00 | 20.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 8.00 | 6.20 | 13.00 | 10.00 | 3.00 | 2.30 | ||

| Years in Primary Occupation (n = 145) | ||||||||||||

| 0-2 years | 26.00 | 17.90 | 9.00 | 6.60 | 4.00 | 2.90 | 9.00 | 6.60 | 3.00 | 2.20 | 18.67 | 0.10 |

| 3-5 years | 20.00 | 13.80 | 5.00 | 3.70 | 7.00 | 5.10 | 5.00 | 3.70 | 2.00 | 1.50 | ||

| 6-10 years | 30.00 | 20.70 | 8.00 | 5.90 | 3.00 | 2.20 | 15.00 | 11.00 | 4.00 | 2.90 | ||

| 11-15 years | 16.00 | 11.00 | 2.00 | 1.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 9.00 | 6.60 | 2.00 | 1.50 | ||

| 16 or more years | 53.00 | 36.60 | 8.00 | 5.90 | 6.00 | 4.40 | 31.00 | 22.80 | 4.00 | 2.90 | ||

| Are you a mandatory reporter? (n = 131) | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 110.00 | 84.00 | 25.00 | 19.20 | 19.00 | 14.60 | 58.00 | 44.60 | 7.00 | 5.40 | 13.90 | 0.00 |

| No | 21.00 | 16.00 | 5.00 | 3.80 | 2.00 | 1.50 | 7.00 | 5.40 | 7.00 | 5.40 | ||

| In the last three years, I have seen an increase in human and/or animal abuse (n = 144) | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 76.00 | 52.80 | 18.00 | 13.40 | 7.00 | 5.20 | 39.00 | 29.10 | 7.00 | 5.20 | 3.94 | 0.68 |

| No | 52.00 | 36.10 | 9.00 | 6.70 | 10.00 | 7.50 | 24.00 | 17.90 | 5.00 | 3.70 | ||

| I don't know | 16.00 | 11.10 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 2.20 | 6.00 | 4.50 | 2.00 | 1.50 | ||

| In the last three years, I have been in a situation where I suspected human or animal abuse (n = 137) | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 115.00 | 83.90 | 25.00 | 19.20 | 18.00 | 13.80 | 61.00 | 46.90 | 5.00 | 3.80 | 22.00 | <.001 |

| No | 22.00 | 16.10 | 3.00 | 2.30 | 2.00 | 1.50 | 8.00 | 6.20 | 8.00 | 6.20 | ||

| In the last three years, I have been in a situation(s) where I suspected human or animal abuse (n = 114) | ||||||||||||

| Animal cruelty & neglect | 63.00 | 55.30 | 7.00 | 6.40 | 17.00 | 15.60 | 32.00 | 29.40 | 4.00 | 3.70 | 24.14 | <.01 |

| Child cruelty & neglect | 31.00 | 27.20 | 11.00 | 10.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 19.00 | 17.40 | 1.00 | 0.90 | ||

| Elder cruelty & neglect | 4.00 | 3.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 2.80 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| Spousal cruelty & neglect | 16.00 | 14.00 | 7.00 | 6.40 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 7.00 | 6.40 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| What made you suspect human or animal abuse (n = 114) | ||||||||||||

| Behavior of people | 62.00 | 54.40 | 13.00 | 11.90 | 8.00 | 7.30 | 34.00 | 31.20 | 4.00 | 3.70 | 1.26 | 0.74 |

| Physical appearance of people | 39.00 | 34.20 | 11.00 | 10.10 | 3.00 | 2.80 | 22.00 | 20.20 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 4.52 | 0.21 |

| Person reported cruelty & neglect | 69.00 | 60.50 | 18.00 | 16.50 | 10.00 | 9.20 | 37.00 | 33.90 | 2.00 | 1.80 | 3.44 | 0.33 |

| Behavior of animal | 38.00 | 33.30 | 4.00 | 3.70 | 8.00 | 7.30 | 21.00 | 19.30 | 4.00 | 3.70 | 7.37 | 0.06 |

| Physical appearance of animal | 60.00 | 52.60 | 7.00 | 6.40 | 18.00 | 16.50 | 29.00 | 26.60 | 3.00 | 2.80 | 22.73 | <.001 |

| Other | 4.00 | 3.50 | 2.00 | 1.80 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.42 | 0.49 |

| Who did you report the abuse to? (n = 99) | ||||||||||||

| Humane agency | 43.00 | 43.40 | 5.00 | 5.20 | 11.00 | 11.30 | 21.00 | 21.60 | 4.00 | 4.10 | 8.32 | <.01 |

| Law enforcement | 34.00 | 34.30 | 8.00 | 8.20 | 3.00 | 3.10 | 21.00 | 21.60 | 2.00 | 2.10 | 2.57 | 0.46 |

| Social work agency | 51.00 | 51.50 | 12.00 | 12.40 | 5.00 | 5.20 | 32.00 | 33.00 | 2.00 | 2.10 | 6.01 | 0.11 |

| Direct supervisor | 17.00 | 17.20 | 6.00 | 6.20 | 3.00 | 3.10 | 8.00 | 8.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.49 | 0.32 |

| The Courts | 14.00 | 14.10 | 2.00 | 2.10 | 4.00 | 4.10 | 7.00 | 7.20 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.92 | 0.59 |

| Other | 14.00 | 14.10 | 4.00 | 4.10 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 5.20 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.91 | 0.59 |

| What was the result of your report of abuse? (n = 98) | ||||||||||||

| Police report was filed | 25.00 | 25.50 | 7.00 | 7.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 18.00 | 18.40 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 10.29 | <.05 |

| Criminal charges filed | 21.00 | 21.40 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 6.00 | 6.10 | 13.00 | 13.30 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.57 | 0.14 |

| Abuser was convicted of cruelty & neglect | 13.00 | 13.30 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 7.00 | 7.10 | 4.00 | 4.10 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 14.50 | <.05 |

| Removal of child | 13.00 | 13.30 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 10.00 | 10.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.27 | 0.35 |

| Removal of partner | 4.00 | 4.10 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 3.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.30 | 0.73 |

| Removal of animal | 23.00 | 23.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 9.00 | 9.20 | 13.00 | 13.30 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 14.83 | <.01 |

| Nothing was done | 22.00 | 22.40 | 7.00 | 7.10 | 3.00 | 3.10 | 11.00 | 11.20 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.90 | 0.59 |

| Other | 8.00 | 8.20 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 5.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.79 | 0.85 |

| Don't know | 30.00 | 30.60 | 6.00 | 6.10 | 5.00 | 6.10 | 14.00 | 14.30 | 5.00 | 5.10 | 9.46 | 0.04 |

| Do you think that others who are mandatory reporters for animal abuse in Ohio are? (n = 88) | ||||||||||||

| Aware they are a mandatory reporter of animal cruelty & neglect | 73.00 | 83.00 | 20.00 | 23.00 | 8.00 | 9.20 | 42.00 | 48.30 | 3.00 | 3.40 | 10.11 | <.05 |

| Aware and know what to do if they suspect animal cruelty & neglect | 33.00 | 37.50 | 8.00 | 9.20 | 1.00 | 1.10 | 22.00 | 25.30 | 1.00 | 1.10 | 6.30 | 0.10 |

| Aware of how to report animal cruelty & neglect | 33.00 | 37.50 | 8.00 | 9.20 | 1.00 | 1.10 | 22.00 | 25.30 | 2.00 | 2.30 | 4.87 | 0.18 |

| Consistent in reporting of suspected animal abuse | 19.00 | 21.60 | 5.00 | 5.70 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 14.00 | 16.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 6.27 | 0.10 |

| Consistent in responding to call(s) for suspected abuse (i.e., check all individuals and animals in the home) | 26.00 | 29.50 | 6.00 | 6.90 | 3.00 | 3.40 | 16.00 | 18.40 | 1.00 | 1.10 | 1.16 | 0.76 |

| Do you think that Ohio House Bill 33 has been effective at increasing protections for humans and animals in Ohio? (n = 110) | ||||||||||||

| Yes, for animals | 19.00 | 17.30 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 5.00 | 4.60 | 10.00 | 9.30 | 2.00 | 1.90 | 9.03 | 0.43 |

| Yes, for humans | 14.00 | 12.70 | 5.00 | 4.60 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 7.00 | 6.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| Yes, for humans and animals | 52.00 | 47.30 | 11.00 | 10.20 | 7.00 | 6.50 | 30.00 | 27.80 | 4.00 | 3.70 | ||

| Not for humans nor animals | 25.00 | 22.70 | 7.00 | 6.50 | 2.00 | 1.90 | 14.00 | 13.00 | 2.00 | 1.90 | ||

| Obstacles to increasing protection for humans and animals in Ohio (n = 101) | ||||||||||||

| I don't know if I am a mandatory reporter | 9.00 | 8.90 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 7.26 | 0.06 |

| I don't know how to recognize human cruelty & neglect | 7.00 | 6.90 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.57 | 0.67 |

| I don't know how to recognize animal cruelty & neglect | 8.00 | 7.90 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.79 | 0.29 |

| I don't know who to call | 18.00 | 17.80 | 6.00 | 6.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 9.00 | 9.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 3.51 | 0.32 |

| If I call, others don't care | 24.00 | 23.80 | 6.00 | 6.00 | 6.00 | 6.00 | 10.00 | 10.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.73 | 0.63 |

| I don't know what to look for | 3.00 | 3.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.97 | 0.40 |

| There are not enough people/agencies to help | 60.00 | 59.40 | 10.00 | 10.00 | 12.00 | 12.00 | 35.00 | 35.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 7.01 | 0.07 |

| Other | 38.00 | 37.60 | 10.00 | 10.00 | 7.00 | 7.00 | 18.00 | 18.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 1.26 | 0.74 |

| On a scale of 1 to 10, how much do you think human and animal cruelty and neglect are linked or related each other? (n = 117) | ||||||||||||

| Mean/SD | 8.54 (2.02) | 7.79 (2.37) | 9.38 (1.28) | 9.00 (1.45) | 7.29 (2.34) | 6.89 | <.001 | |||||

DOI: 10.55167/31d695a3bd79

Aviva Vincent (corresponding author), PhD, LSW, Assistant Professor of Social Work, College of Health, Cleveland State University, Cleveland, Ohio 44115, USA. E-mail: [email protected]. ORCID: 0000-0003-2527-940X. ↩︎

Eunice Lee, PhD, Assistant Professor of Social Work, College of Health, Cleveland State University, Cleveland, Ohio 44115, USA. E-mail: [email protected]. ORCID: 0000-0003-4285-7857. ↩︎

Alana Van Gundy, PhD, JD., Lecturer, Department of Sociology, College of Arts & Sciences, The Ohio State University, 1885 Neil Ave, Columbus, Ohio 43210, USA. E-mail: [email protected]. ORCID: N/A. ↩︎

Lauren Caswell, Biology student, Cleveland State University, Cleveland, Ohio 44115, USA. ORCID: N/A. ↩︎

Linda Quinn, PhD, Professor, Department of Mathematics and Statistics, Cleveland State University, Cleveland, Ohio 44115, USA. ORCID: 0000-0002-4314-6072. ↩︎